Hacker Madness

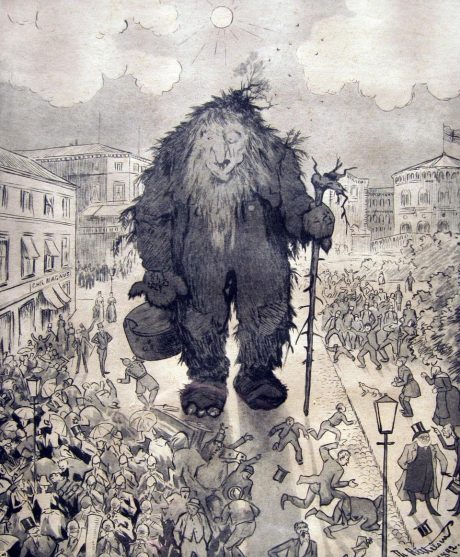

Hackers induce hysteria. They are the unknown, the terrifying, the enigma. The enigma that can breach and leak the deepest secrets you’ve carelessly accreted over the years in varied fits of passion, desperation, boredom, horniness, obsession, and jubilation on your computers, phones and the internet. Maybe you’re the government, maybe you’re just some innocent schmuck—maybe you’re both. Maybe you don’t deserve to be exposed, maybe you do. The common fear is that you will never know who exposed you. Is it a he, a she, or an it? The FBI? The NSA? You feel vulnerable and it feels as though what happened is black magic because you understand nothing about how it was done. Terrifying, fascinating, excruciating black magic, practiced by an enigma.

Or maybe you do know how the enigma did it, and you feel stupid: because the enigma exposed your lazy information security—maybe because your password was just “1234”, or your birthday, or maybe you logged into a public Wi-Fi network without VPN, and maybe, just maybe, you used the same password for all your accounts. You’re a moron for doing that, and you know it; but it never occurred to you that anyone would bother to hack you at Starbucks. You’re hysterical over an enigma that could be anywhere in the world; or perhaps your roommate, child, or lover in your own home.

I regularly observe this hysteria. I’m a defense lawyer who represents hackers in federal courts across the United States. I’m writing this in an airport in Kentucky after the sentencing of a client. He and his colleague hacked a cheap high school football fan website to protest the rape of a minor in Steubenville, Ohio by members of the high school football team. They posted a video of my client in a Guy Fawkes mask decrying the rape. They helped organize protests over the rape in the town. It attracted national media attention. It led to the federal government indicting my client for felony computer crime. The federal government never prosecuted anyone involved in the rape.

My client was part of a movement protesting what they viewed as the small town’s attempted cover up of the extent of the rape. Much ire was directed at the local county prosecutor (not to be confused with the federal prosecutors in Kentucky who indicted my client) who initially handled the case. The perception was that she was intentionally limiting the scope of the prosecution because she was closely connected to the football team through her son. Social media postings of football team-members seemed to implicate more than the two football players she initially went after. Eventually, she recused herself from the case. After this, the town’s school superintendent, the high school principal, the high school wrestling coach, and the high school football coach were indicted on various felony and misdemeanor charges including obstruction of justice and evidence tampering. It’s unlikely any of this would have happened without the attention my client, along with many others, helped bring to the case

The local prosecutor wasn’t even the one who got hacked. That person, perhaps out of fear, stayed out of it. Yet this prosecutor, in a letter submitted to the court at my client’s sentencing, breathlessly condemned my client as a terrorist—yes, a terrorist—for bringing attention to the sordid details of the attempted cover-up of the extent of a 16-year-old girl’s rape. A rape that involved the girl incapacitated by alcohol being publicly and repeatedly penetrated and urinated on by members of the football team, their jocular enthusiasm captured in the photos they posted on social media. No one died, no one except the rape victim was physically hurt, yet my client was called a terrorist and thrown in jail because a $15 website with an easily guessed password got hacked. All of this, because of the embarrassment, the shame, and the vulnerability—not that of the rape victim, but of a town whose dark secrets had been breached and leaked.

My client got two years – the two rapists got one and two years respectively. My client didn’t physically or financially harm anyone. At best the damage was reputational, but that was self-inflicted by people in the town. My client didn’t rape a minor. Metaphorically, the town did, and in reality, members of its high school football team did. Nonetheless, in that case and most I deal with, the federal criminal “justice” system hysterically treats hackers on par with rapists and other violent felons.

Including the Steubenville rape case, I’ve now had two clients called “terrorists” in open court. In the second case, the former boss of a client of mine, in a moment that almost made me laugh out loud in court, called him a terrorist at his sentencing. I suspect the boss was a bit jealous of my client’s journalistic talent and was ruefully avenging his own feelings of inadequacy and loss of control. This particular client had quit his job in a pique after justifiably accusing his boss at the local TV station of engaging in crappy journalistic practices. After departing his job, he helped hack (allegedly) the LA Times website, owned by the same parent company and sharing the same content management system; a few words were changed in a story about tax cuts.

The edits— the government liked to refer to it as the “defacement” — were removed and the article restored to its original state within forty minutes. For this, the sentencing recommendation from pre-trial services was 7 ½ years, the government asked for 5, and the judge gave him 2. Again, no one was physically hurt, the financial loss claims were dubious, and the harm was reputational, at best. But my client was sentenced more seriously than if he’d violently, physically assaulted someone. In fact, he’d probably have faced less sentencing exposure if he’d beaten his boss with a baseball bat.

Unsurprisingly, his actions were portrayed as a threat to the freedom of the press. There was some pious testimony from an LA Times editor about the threat to a so-called great paper’s integrity. But when the cries of terrorism are stripped away, a more mundane explanation for all the sanctimony emerges: the “victim’s” information security sucked. They routinely failed to deactivate passwords and system access for ex-employees. After the hack, they discovered scores of still active user accounts for ex-employees that took them months to sort through and clean up. They stuck my terrorist client with the bill for fixing their bad infosec, of course. All of this, because of the embarrassment, the shame, and the vulnerability–not of an employee, but that of a powerful organization.

Another one of my clients who lived in a corrupt Texas border town was targeted by a federal prosecutor. The talented young man had committed the egregious sin of running a routine port scan on the local county government’s website using standard commercially available software. Don’t know what a port scan is? Don’t worry, all you need to know is that it’s black magic. This client had also gotten into it a tiff with a Facebook admin, exchanged some testy emails with the admin, but walked away from it while the admin continued to send him emails. A routine internet cat-fight of little import that wouldn’t raise eyebrows with anyone mildly experienced with the internet’s trash talking and petty squabbles.

But this client, like most of my clients, was purportedly affiliated with Anonymous. This led to an interesting state of affairs that demonstrates both the fear and the contempt the government has for enigmatic hackers. In essence, the FBI detained my client and threatened him with a felony hacking prosecution unless he agreed to hack the ruthlessly violent Mexican Zeta Cartel. Fearing for his loved ones and himself, my client sensibly declined this death wish. But the FBI persisted. The FBI specifically wanted a document that purportedly listed all the U.S. government officials on the take from the Zetas. No one even knew if this document existed, but the FBI didn’t care much about that fact. After my client declined, he was charged with 26 felony counts of hacking and 18 felony counts of cyberstalking based on his interaction with the Facebook admin.

Naturally, this case was brought to my attention. After examining the Indictment and engaging in a few interesting discussions with the federal prosecutor, my client pleaded guilty to a single misdemeanor count of hacking related to his port scanning of the local government website. Better to take a misdemeanor than run the risk of a federal criminal trial where the conviction rate is north of 90%. But the fact that this hysterical prosecution was brought in the first place reflects poorly on the exercise of prosecutorial discretion about hacking on the part of the Department of Justice. Again, no one was hurt, no one lost money, but my client was facing a maximum of 440 years in jail under the original Indictment.

My hands down favorite example of hacker-induced hysteria was directed at me and my co-counsel in open court. I couldn’t hack my way out of a paper bag, but prosecutors love to tar me by association with my clients. In this instance, on the eve of trial on a Friday in open federal court, the prosecutor—along with the FBI agent on the case— accused my co-counsel and me of hacking the FBI, downloading a top-secret document, removing the top-secret markings on it, and then producing it as evidence we wanted to use at trial. Co-counsel and I were completely baffled, exchanged glances, and then told the court we would give the court an answer on Monday as to the document’s origins—and to this criminal, law license jeopardizing accusation.

It turns out we’d downloaded the document in question from the FBI’s public website. The FBI had posted the document because it was responsive to a Freedom of Information Act request. The FBI had removed the top-secret markings in so doing. Needless to say, we corrected the record on Monday. Pro-tip for rookie litigators: If your adversary produces a document you have a serious question about, it’s best to confer with your adversary off the record about it before you cast accusations in open court that implicate them in felony hacking and Espionage Act violations. But, such is the hysteria that hacking induces that it spills over to the lawyers that defend them. How many lawyers who defend murderers are accused of murder?

The feelings of vulnerability, fear of the unknown, and embarrassment that feed the hysterical reaction to hackers also lead to the fetishizing of hackers in popular culture. T.V. shows like Mr. Robot, House of Cards, and movies like Live Free or Die Hard, where the hackers are both villains and heroes, all exacerbate this fetish. And this makes life harder for me and my clients because we have to combat these stereotypes pre-trial, at trial, and during their incarceration should that come to be. Pre-trial, my clients are subjected to irrational, restrictive terms of release that rest on the assumption that mere use of a computer will lead to something nefarious. During trial, we have to combat the jury’s preconceptions of hackers. And if and when they’re put in jail, convicted hackers are often treated on par with the worst, most violent felons. Almost all of my incarcerated clients were thrown in solitary for irrational, hacker-induced hysteria reasons. But those are stories for another day.

The hysteria hackers induce is real, and it is dangerous. It leads to poorly conceived and drafted draconian laws like America’s Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. It distorts our criminal justice system by causing prosecutors and courts to punish mundane computer information security acts on par with rape and murder. Often, I receive phone calls from information security researchers, with fear in their voice, worried that some routine, normally accepted part of their profession is exposing them to felony liability. Usually I have to tell them that it probably is.

And the hysteria destroys the lives of our best computer talents, who should be cultivated and not thrown in jail for mundane activities or harmless pranks. All good computer minds I’ve met do both. Thus, not only is hacker-induced hysteria detrimental to our criminal justice system in that it distorts traditional notions of fairness, justice, and punishment based on irrational fears. It is fundamentally harmful to our national economy. And that should give even the most ardent defenders of the capitalistic order at the Department of Justice and the FBI pause, if not stop them dead in their tracks, before pursuing hysterical hacking prosecutions.

The best proof that this hysteria is unwarranted and unnecessary most of the time is the fate of persecuted hackers and hacktivists themselves. Most of those arrested for pranks, explorations, and even risky, hard-core acts of hacktivism aren’t a detriment to society, they’re beneficial to our society and economy. After their youthful learning romps, they’ve matured their technical skills—unlearnable in any other fashion—into laudable projects. Robert Morris was author of the Morris Worm. He’s responsible for one of earliest CFAA cases because his invention got out of his control and basically slowed down the internet, such as it was, in 1988. Now he’s a successful Silicon Valley entrepreneur and tenured professor at MIT who has made significant contributions to computer science. Kevin Poulsen is an acclaimed journalist; Mark Abene and Kevin Mitnick are successful security researchers. And those’re just the old-school examples from the ancient—in computer time—1990’s.

Younger hackers are doing the same. From the highly entertaining hacker collective Lulzsec, Mustafa Al Bassam is now completing a PhD in cryptography at University College London; Jake Davis is translating hacker lore, culture, and ethics to the public at large; Donncha O’Cearbhaill, is employed at a human rights technology firm and is a contributor to the open source project Tor (no relation); Ryan Ackryod and Darren Martyin are also successful security researchers. Sabu, the most famous member of Lulzsec, of course, has enjoyed a successful career as a snitch, hacking foreign government websites on behalf of the FBI and generally basking in the fame and lack of prison time his sell out engendered. And I’m not going to talk about the young, entertaining hackers that haven’t been caught yet. But the ones I care about, the ones I think are important, aren’t interested in making money off your bad infosec. They’re just obsessed by how the system works, and a big part of that is taking the system apart. Perhaps I share that with them as a federal criminal defense lawyer.

All these hackers exemplify the harms that hysteria can have: misdirecting the energy of exactly the people who can help test, secure and transform the world we occupy in the name of public values that we share: values our own government should be defending, instead of destroying.