Right To Repair

An interview with R2R advocate Kyle Wiens

In 2023, Colorado farmers won back the right to repair their own tractors. John Deere, one of the world’s largest producers of agricultural equipment, sold machines with proprietary software that made independent repairs almost impossible. Locked out of their equipment’s operating systems, some American farmers hacked their way in. Others turned to the political and judicial systems. Supporters of Colorado’s Consumer Right To Repair Agricultural Equipment bill faced stern resistance and high-dollar lobbying—not only from John Deere, but also from large technology companies and the trade associations that represent their interests. Clearly, there was more at stake than tractors.

This case, featuring a veritable icon of America’s heartland, is emblematic of the broader Right to Repair (R2R) movement. The premise of the R2R movement is simple: to ensure that individuals and independent repair shops have the information, tools, and parts to fix their own stuff. The stakes of this fight are personal and planetary. Landfills across the world are overflowing with e-waste and unfixable technologies. And the human and environmental consequences are only getting worse.

A significant actor in this struggle is Kyle Wiens, chairman of the advocacy group Repair.org and founder and CEO of iFixit.com, a free online repair manual. Long before Wiens slung his first stone at Big Tech, his grandfather would take him to thrift shops to buy printers and other devices to take apart and reassemble. Those childhood experiences instilled a keen interest in technology. As the tinkerer grew into an engineer, Wiens became increasingly concerned about where the treadmill of innovation and obsolescence was taking us. He now stands as a key player in the Right to Repair movement, leading initiatives, driving legislation, and speaking widely on the importance of repairing what is broken.

Limn sat down to speak with Wiens about his life and work. Below are excerpts from our conversation on May 15, 2024.

Man driving a John Deere tractor, pigs and corn crib in the background, Iowa / WKL. Iowa, 1963. BY WARREN K. LEFFLER, COURTESY OF U.S. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Towns Middleton Kyle, how did you get involved with the Right to Repair movement?

Kyle Wiens We started iFixit because we were interested in technology and fixing things and trying to pay our way through college. After graduating, my co-founder and I traveled around the world. We went to Ukraine and Russia and all over Africa, investigating: How do people use things? What are the needs globally? I went to Agbogbloshie, the electronics market and scrapyard in Accra, Ghana. Around it, there are all these repair markets, where the workers were making more money than the kids burning electronics. When we asked them how they learned to repair things, they said, “We just Google it.” This inspired us to think: what could we do to transform the jobs burning copper and move them up the food chain?

Ghanaians working in Agbogbloshie, a suburb of Accra, Ghana, 2011. en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Agbogbloshie.JPG.

Creative Commons License (CC0 1.0). COURTESY OF MARLENENAPOLI

So the idea that emerged was: we’re going to make repair manuals for everything and put it all out there for free online. We’ll write repair manuals for all the Logitech products and show them that this is a better way. We thought they would instantly see the obviousness of what we were doing and want to work with us. We spent ten years tilting at that windmill and completely failing.

Then, we started working with the Global Electronics Council’s EPEAT environmental standards and trying to use those benchmarks to influence manufacturers. But we quickly realized that the regulatory process had been totally co-opted by the manufacturers. There was this big moment in 2012 when Apple rolled out the first new MacBook with glued-in batteries. There’s language in the Green Laptop Standard that said that a laptop must be readily disassembled with commonly available tools. So we went to the Global Electronics Council and said, “This laptop does not meet that standard.” We disassembled it for them and showed them the process. I was like, “You can’t do this in a non-destructive fashion.” But then Apple showed them that there was a technique. My theory is that they just took a sledgehammer to it, like, “Look! We took it apart. It didn’t say it needed to be reversible.”

We got the White House involved. The city of San Francisco said they weren’t going to buy Apple products for a little while. But, ultimately, we realized that engaging these environmental standards was futile. There was too much money on the line. The manufacturers were sending lawyers into the process, and their only job was just to make sure the standards didn’t get better.

We had tried collaboration and the carrot approach. It didn’t work. We realized, OK, we’re going to have to pass laws. So I started building the coalition and looking for an easy win. The easy win that we identified was the cell phone unlocking bill. When the Library of Congress decided that unlocking cell phones without the carrier company’s permission would violate copyright laws, the US became, in 2012, the only country in the world where it was illegal to unlock a cell phone, which is ludicrous to anyone who travels internationally. So we helped augment a White House petition that Sina Khanifar put together. The White House replied, and basically said, “Yeah, we agree. Congress should do something.” It was kind of common sense. And it was a relatively easy lift to get it through Congress. [The Unlocking Consumer Choice and Wireless Competition Act officially passed in 2014.] OK, cool, we passed a bill. It wasn’t a repair bill, but it had huge positive environmental impacts. After that, it took us another nine years to get enough momentum to actually start passing state-level Right to Repair bills. We have introduced hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of bills, and we’ve passed seven.

Assorted Camera Parts. BY KEI SCAMPA VIA PEXELS

TM Why the long odds?

KW The corporations registered to lobby against us in New York State alone have a cumulative stock market value (market cap) of more than ten trillion dollars. It’s very easy to stop legislation. The lobbyists are pretty savvy. They tend to stop it quietly behind the scenes. It dies in rules, or it dies without a vote. We’ve gotten very few up or down votes that we’ve lost.

Ashley Carse In a 2023 interview with the New York Times, you mentioned the cultural prohibition that exists around taking technologies apart. When you brought an iPod into a place where kids were hanging out and asked them to open it up, they looked at you like you were crazy. That seems to speak to this question about how you change the culture around repair.

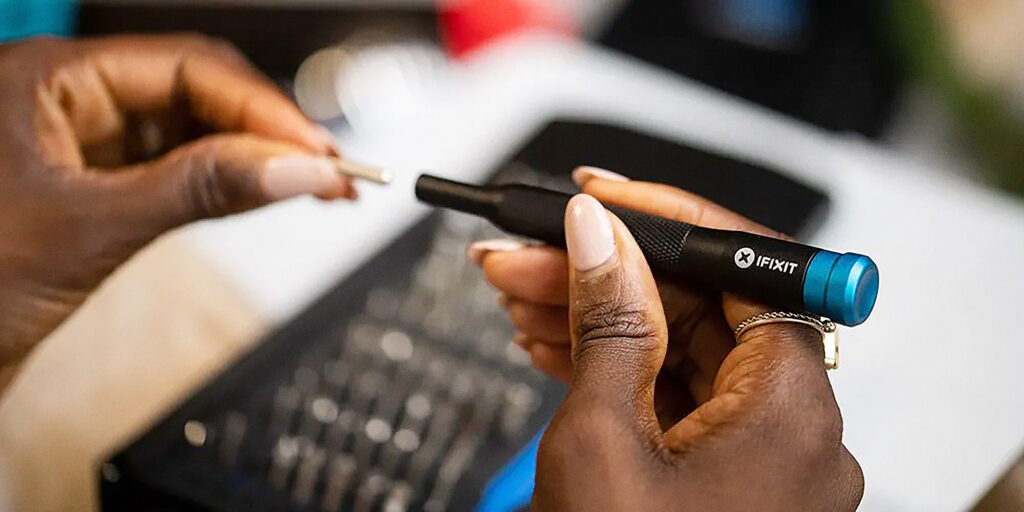

iFixit tools at work. COURTESY OF KYLE WIENS

KW We brainwash kids into not taking things apart. I’m aware that part of raising children is, “Please don’t take that thing out of the drawer.” But somewhere in that process we convince them not to open anything up. We remove that curiosity. And it’s baked deep into the psyche. You have to reverse that. It doesn’t take much. Once you give them a printer and a screwdriver, they have a blast. And they never stop. That’s a life-changing moment that ninety-nine percent of the population never gets.

TM I want to ask you a more conceptual question. Much of what you’re up against could be called planned obsolescence. But there are other kinds of obsolescence out there, right?

KW The framing of planned obsolescence really gets manufacturers’ hackles up. This is justified, because there is not a smoke-filled room where they’re sitting there saying, “How are we going make our product die in exactly warranty-plus-one-day?” But they are choosing to prioritize investment in new software features rather than security updates for seven-year-old devices. That’s not mal-intent. But it is a mal-allocation of resources with lots of long-term societal implications.

AC You were talking about how you traveled to Russia, Ukraine, and Ghana. But it seems like a lot of iFixit and the Right to Repair movement has been focused on North America and the North Atlantic world. How do you think about obsolescence and repair outside of that context?

KW The number one requirement for me—and all the Right to Repair movement—is that the information has to be freely available. A dollar is too much. A log-in barrier is too much. The information has to be dispersed as widely as the products are. I know a refurbisher in South Africa where they track the serial numbers of computers, and they have sold the same computer three, four, five times. The best way to get technology into the hands of people that need it—to bridge the digital divide—is to make the product last long enough for it to be able to get there.

Gökçe Günel What’s the biggest thing on your agenda these days?

KW Parts pairing is number one. [This is the growing trend of manufacturers incorporating software into their products to block would-be repairers from using salvaged parts.] We’ve spent the last six to nine months stymying Apple on that. We got two laws passed. Then we’re working on ratcheting up for Right to Repair laws for next year.

If you take the long-term view and ask, “What’s the inflection point that’s happening around obsolescence or short-lived products?” Right now, it’s the integration of software into things that didn’t have software before. The addition of a microchip is a fundamental pivot point. It prevents things from lasting. Why is the lifespan of a refrigerator or a washing machine only seven years? It’s because of a capacitor or something inside it that didn’t need to be there in the first place. We have to push back against that and try to get as little electronics in things as possible. But then, when we do, we’ve got to find ways of repairing those.

Another important area is consumer behavior research. How do we get people to bias toward higher-quality, longer-lasting products? There’s been great work at PLATE, the Product Lifetimes and the Environment Conference, showing that if people know something is repairable, if they have information up front, it can change people’s buying behavior. This would then drive product designers to invest in making things modular and repairable. The French Repairability Index that has come out is hugely effective in this area. Until we fix the signal at purchase time, the problem is only going to keep getting worse.

But to your question, Gökçe, of where we are at present: You get the sense that we are just wandering through the wilderness, trying to nudge the world in a better direction and pulling on every lever that we possibly can in order to get there. ■