Deprecating Death

Can the war on life be rendered obsolete?

Men are nothing in modern war unless they are equipped with the most effective devices for killing and maiming the enemy’s soldiers and thoroughly trained in the use of such implements. History proves that an effective implement of war has never been discarded until it becomes obsolete.

—William L. Sibert, first director of the US Chemical Warfare Service, 19211

For something so inescapable, there’s a great deal of creativity in death. New ways of killing are being invented all the time. At the frontier of this invention—and its accompanying forms of obsolescence—is the pesticide industry. The industry’s typical cycle of innovation and obsolescence begins with the application of something that kills a pest within an agricultural monoculture in which its natural predators have been removed. At first, the pesticide works. A generation of pests is largely exterminated. But the survivors have a predator-free source of food available, if they’re able to adapt. Evolutionary pressures drive pests to develop resistance, and soon, farmers find themselves needing to apply more and more pesticide to achieve the same level of pest control, until new products emerge to reset the balance of forces, and the game begins again.

It’s tempting to normalize this cycle, to imagine that obsolescence emerges as a pure function of ecology: following the natural logic of evolution, the pest develops resistance, and then the compound to which it is immune is declared obsolete. This thinking, however, overlooks other forces in play. To see why, it’s worth looking at a field that has matured alongside the pesticide industry: the arms industry. First though, a literary interlude.

Written in 1989, J. G. Ballard’s “War Fever” is a short story set in a conflict-riven Beirut. Blue-helmeted UN soldiers tend to the wounded, arrange for the orphaned to be fostered, and debrief and photograph the survivors of atrocities “like prurient priests at confession.” Amid the suffering, one militant wonders:

What if the living were to lay down their weapons? Suppose that all over Beirut the rival soldiers were to place their rifles at their feet, along with their identity tags and the photographs of their sisters and sweethearts, each a modest shrine to a ceasefire?2

Eventually, it emerges that this Beirut is not what it seems. War on Earth is over because, in just the same way as smallpox has been eradicated (the World Health Organization “deliberately allowed smallpox to flourish in a remote corner of a third-world country, so that it could keep an eye on how the virus was evolving.”), so too the UN has kept a small laboratory for hate and conflict in the Middle East, so that the rest of the world could be free from war. In this laboratory, ceasefires have broken out. They are resolved by removing the peacemakers and rekindling the conflict. Ballard’s story ends with war finally breaching the safety zone, ready to infect a world immunologically naive to its horrors.

![Man [and Chemicals] Working in a Rice Field.](https://limn.press/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/pexels.comphotophoto-of-a-man-working-in-a-rice-field-13944483-666x1024.jpg)

Man [and Chemicals] Working in a Rice Field. BY FERDOUS HASAN VIA PEXELS

In Ballard’s fictional universe, the forces that decide whether participants have developed a resistance to conflict are those “prurient priests,” the UN, who need a permanent war as insurance for a perpetual peace. They’re there merely to keep Darwinian forces in motion. In this task they prove too successful. Violence pierces the UN perimeter, in what we come to understand is the world’s final lab leak. This science-for-science’s-sake approach to war ultimately provides a clue to understanding obsolescence. But unlike Ballard’s Beirut, the real world has capitalism, and capitalism makes all the difference.

In the real Middle East, one sees clear intersections of capitalist interests and emerging technologies of death in Gaza, where the Israeli arms industry continues to pioneer and field-test weapons. A recent report by Al Jazeera, a news agency banned in Israel, quotes Antony Loewenstein, who observes that “in every war against Gaza a range of weapons and surveillance tech has been deployed against the Palestinians which is then marketed and sold to huge amounts of nations around the world.” Loewenstein arrives at this observation through meticulously documented research in his award-winning study of the Israeli defense industry, its international schools for police, and its cyber warfare tools. The title of his book: The Palestine Laboratory3.

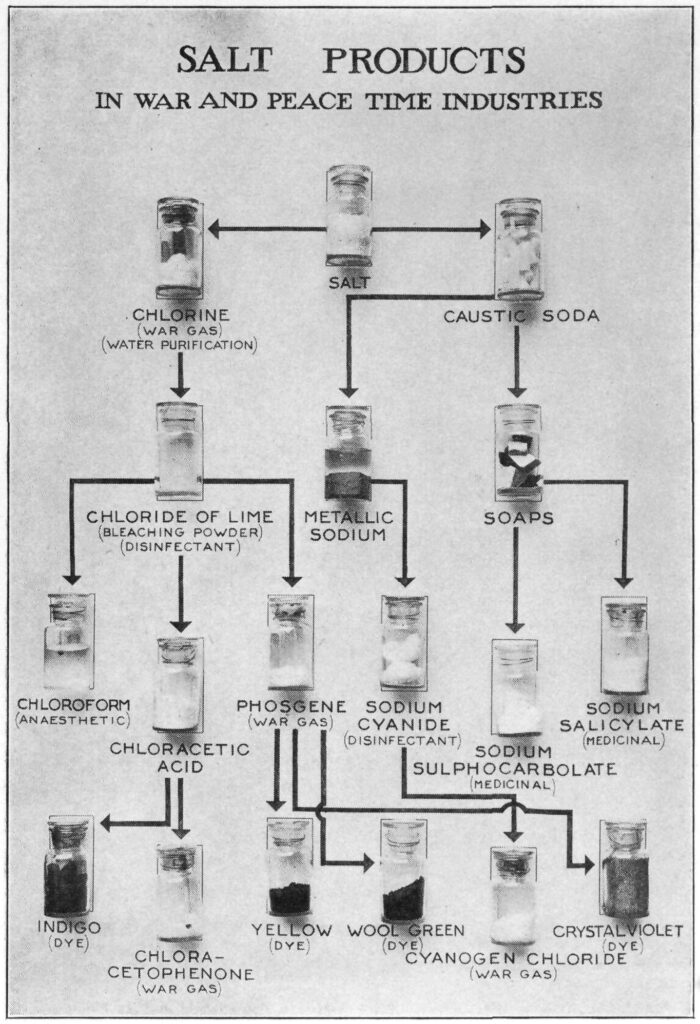

Killing salts—uses of salt products in war and peace. 1922. IMAGE BY UNITED STATES CHEMICAL WARFARE SERVICE4

“In these cycles where resistance begets obsolescence begets innovation, war is, necessarily, a permanent state of crisis and fixing and profit maximization.”

The divergence between “War Fever” and The Palestine Laboratory presents an opening for understanding obsolescence. Obsolescence figures not as some inflection point within the calculus of natural selection; ecological resistance matters less than economics. It’s worth remembering that both the arms and pesticide industries are industrial concerns. They’ve often been one and the same.

The manufacturers that produced chemical weapons during World War I were also in the business of producing pesticides. The development of one application often begot the other. The pursuit of explosives and deadly gases birthed the world’s first synthetic organic pesticide, paradichlorobenzene5. Early chemical weapons were tested on insects, and during WWI fumigants used in the French fruit industry, like hydrocyanic acid, were tested on humans6. As insecticides morphed into chemical weapons and vice versa, the consequences of WWI on the pesticide industry were seismic—not least in transforming the sleepy American dye manufacturing industry into a global powerhouse dominated by two firms, National Aniline & Chemical, and DuPont. Both of these companies sought profits that might approach the scale of Germany’s chemical giant IG Farben, which in the interwar years became Europe’s largest corporation, and a direct backer of the incipient Nazi war machine7. History has thus rendered the respective industries of killing humans and killing pests not just analogous, but also homologous.

In these cycles where resistance begets obsolescence begets innovation, war is, necessarily, a permanent state of crisis and fixing and profit maximization. Flipping through pesticide industry archives reveals names like Javelin, Bravo, Captain, Ammo, Boomerang, Warrior and, when that became obsolete, Warrior II with Zeon Technology®. To combat resistance, new pesticide technologies are marketed. Just as in the arms industry, obsolescence happens not only in the field, but also in the product catalogue.

“DDT is good for me-e-e!” 1947. COURTESY OF SCIENCE HISTORY INSTITUTE

The pace is quickening. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the lifespan of a commercial pesticide was around forty years. Very few pests were observed to develop resistance to the arsenal of toxins produced through agricultural chemistry. But early chemical salt pesticides were problematic, both because they were universally lethal to animals and because so much was applied that it was hard for humans to avoid getting poisoned too. The advent of synthetic pesticides like DDT promised far lower rates of application, but caused resistance to soar. With higher resistance came more market opportunities to declare a pesticide obsolete. One observer notes that “prior to 1946, a new resistant species emerged every two to five years. Between 1946 (one year after the introduction of DDT) and 1954, the rate rose to an average of one to two species annually; between 1954 and 1960 the rate was 17 per year.”8

Pesticide inventors have found creative paths to manufacture new kinds of obsolescence. Back at the beginning of the discovery of pesticide resistance, a novel idea was proposed to deal with the problem of the resistant San Jose scale, an invasive insect wreaking havoc on North American agriculture. Rather than change the weapon, it might be necessary to transform the victim. In a 1908 paper, one author proposed inducing an ordinary “scale to cross with the immunes and thus return to the normal susceptible population.”9 The release of modified insects in the twenty-first century, notably mosquitoes that are either sterile or contain a genetic modification that causes the insect to die before it reaches adulthood, is the latest iteration of this idea.

“Since industrial pesticide manufacture is a war without end, the only logical way to stop cycles of innovation and obsolescence is an agroecological armistice…”

Pioneering this new frontier of profitability, the pesticide business has become the “crop protection industry.” A decade ago, its profit center moved from the manufacture of new killer chemicals toward the licensing of plants that can themselves manufacture pesticides. Cotton, for instance, was genetically modified to exude Bacillus thuringiensis toxins to ward off predatory insects. Inevitably, these pests developed resistance. The next generation of these plants are now being engineered to also produce specific RNA inhibitors, configured to disrupt the juvenile stage of a target insect.

The pesticide industry can see the big picture. Just as with the arms industry, where bullets and guns are a reliable but not terribly profitable source of income, the money now is in data, surveillance, and cyber warfare. Insects will always develop resistance, but the long-term royalties come from plant platforms that can be updated yearly with the latest cassettes of genetic information. The problem for the pesticide industry is that plant varieties are subject to law that predates the digital era. You can study this complaint in a paper aptly entitled Obsolescence in Intellectual Property Regimes, penned by a University of Iowa law professor and a research fellow at Pioneer Hi-Bred (a subsidiary of Corteva, the agricultural spin-off of DowDuPont).10 Plant varieties can be protected as intellectual property and subject to experimentation by farmers. But, the authors offer, “‘variety’ is an artificial construct that developed as a pragmatic response to marketplace needs, and as a convenient legal construct to facilitate consensus on intellectual property rules.” The protection of varieties inhibits innovation, they argue, because it allows farmers to tinker and develop their own, rendering the industry’s huge investments in genetics far less lucrative. Instead of protecting varieties, industry representatives sketch an intellectual property regime that understands plants less as stable beings, and more as living data sets.

If this enclosure of knowledge marks another expansion of capitalist frontiers, it also entails a discernable management of obsolescence. Insects may develop resistance to the latest advances in “crop protection.” Individual pesticides may become obsolete at the moment their replacement is brought to market. But the product line can live forever.

A happy ending here would be (recalling Ballard) an end to the war on the web of life. Since industrial pesticide manufacture is a war without end, the only logical way to stop cycles of innovation and obsolescence is an agroecological armistice, in which biodiverse ecosystems are nurtured and insect populations managed not through annihilation but through ecological balance under a postcapitalist society.

Unfortunately, the chemical industry has behind it the awesome power of the state, finance, and philanthropy. With that backing, it remains remarkably adept at escaping regulatory control. Given recent successes by the pesticide industry to evade even the lightest attempts to restrict its use in Europe, as well as the growth of the industry through Chinese capital, and Bill Gates’s deep pockets bringing the Green Revolution to Africa, experiments to generate profit from death are constantly being expanded. As a result, we will continue to enjoy new ways of dying for many years to come. ■

- Amos A. Fries and Clarence J. West, Chemical Warfare (McGraw-Hill, 1921), ix. ↩︎

- J. G. Ballard, The Complete Short Stories. (W. W. Norton, 2009), 1147. ↩︎

- Antony Loewenstein, The Palestine Laboratory: How Israel Exports the Technology of Occupation around the World (Verso Books, 2023). ↩︎

- What the Chemist Has Done and May Do For Them in War and Peace (National Research Council and United States Chemical Warfare Service, 1922), 17. ↩︎

- Frank A. Von Hippel, The Chemical Age: How Chemists Fought Famine and Disease, Killed Millions and Changed Our Relationship with the Earth (University of Chicago Press, 2020), 150–158. ↩︎

- Edmund Russell, War and Nature: Fighting Humans and Insects with Chemicals from World War I to Silent Spring, Studies in Environment and History (Cambridge University Press, 2001). ↩︎

- Frank A. Von Hippel, The Chemical Age: How Chemists Fought Famine and Disease, Killed Millions and Changed Our Relationship with the Earth (University of Chicago Press, 2020), 215–246. ↩︎

- Andrew J. Forgash, “History, Evolution, and Consequences of Insecticide Resistance,” Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology 22, no. 2 (1984): 179. ↩︎

- Forgash, “History, Evolution, and Consequences,” 178. ↩︎

- Mark D. Janis and Stephen Smith, “Obsolescence in Intellectual Property Regimes,” University of Iowa Legal Studies Research Paper, no. 05–48 (2006). ↩︎