Confessions of an Art World Ghost

The museum’s army of invisible labor

This essay is about the administrative ghosts that haunt the art world. If you’ve had the good fortune of never having worked in an art museum or gallery, you may be unaware that such workplaces are profoundly hierarchical, and that there’s an army of assistants, associates, and coordinators behind every curator whose name gets emblazoned on an exhibition press release, wall text, or catalogue.

There’s an army of upper administrators and board members in front of every curator as well—ones who shape the character and politics of the art that said curator is even allowed to exhibit. And there’s an army of art handlers and security guards and janitors behind this entire administrative apparatus—one that’s rarely, if ever, the subject of any reflection within the art world.

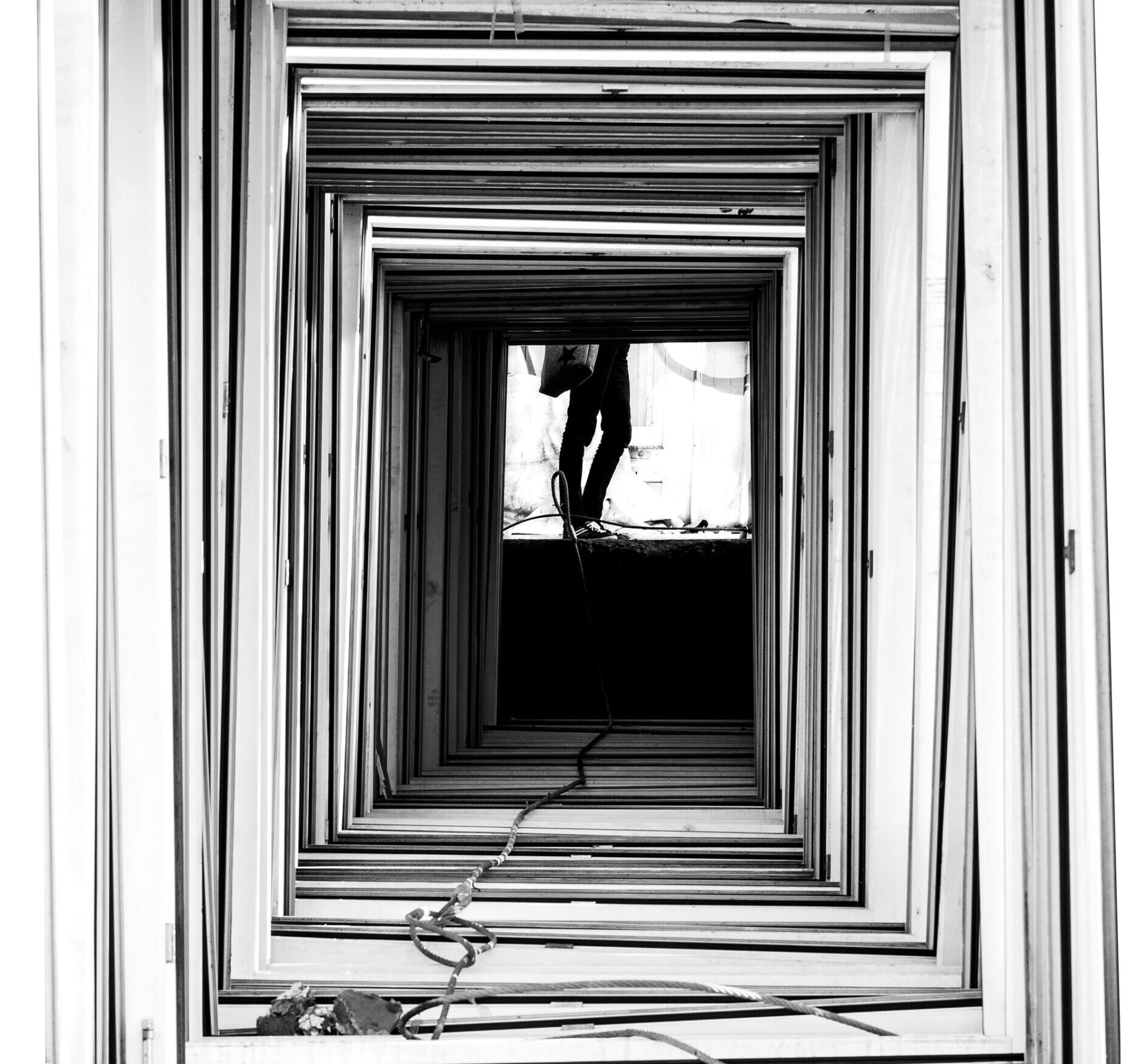

In other words, art museums and galleries, like so many other late capitalist enterprises, run on invisible labor: armies and their armies. They aren’t really invisible, though, because everyone in the art world is aware of them. Most of them just ignore the ghosts.

This story concerns a young curatorial assistant at a very well-known New York-based art museum, ghostwriting catalogue essays for a couple of very well-known art world personae. If you’re in the art world yourself, you may be able to divine the setting and main characters. If you’re not, you needn’t care about these people. Either way, none of what follows is a secret.

This is a true story.

“Quote Susan Sontag,” the museum’s executive director, A., orders as I prepare to write her catalogue essay on the German photographer Katharina Sieverding. It’s a clichéd request, a basic-bitch move that any curator or critic worth their salt should avoid when writing about photography—a gesture that even I, a twenty-three-year-old recent college graduate at the time, recognize as at once trying too hard and not hard enough. “OK,” I reply, scribbling “Quote Sontag” in my notebook.

A.’s demand to invoke this particular public intellectual is ironic, given that just a few months prior, the museum’s chief curator, K., had tasked me with writing a dossier of letters from various luminaries in support of his visa application. Included in the record was a missive from his pal Susan Sontag, a friend so dear she apparently couldn’t be bothered to author her own recommendation, which meant that I had to do it. Having already written in Sontag’s voice, I was now being told to cite Sontag in A.’s voice.

It’s enough to make you lose respect for any Writer, even all Writers, the ease with which such an allegedly creative pursuit can be delegated and rendered into grunt work, a mechanical reproduction of cliché that somehow amplifies cliché’s essence as mechanical reproduction. Writing is labor, but nothing makes you more aware of that material fact than ghostwriting, the kind of writing you perform knowing you’ll never get the authorial credit that is, in truth, the only thing glamorous about writing.

“Sarah’s my writer,” A. once bragged to a famous person who visited the museum. I don’t remember who it was (there were a lot of famous people who visited the museum), but I recall A. saying this by way of introduction. Instead of telling said famous person that I was a curatorial assistant, which was the job I’d been hired to do, she claimed me as a tool, her tool, an automatic text-generator, a metaphorical mouthpiece for the pearls of wisdom raining from her margarita-loosened lips.

It was sometime between 2003 and 2005, a couple of decades before chatbots roamed the internet. I was terrible at even the most basic administrative tasks, my brain a sieve for details of any kind. In college I had wanted to be a filmmaker. Every film I made was light on meaning and heavy on voiceover. My advisor, herself an under-recognized auteur of experimental cinema, gently urged me to consider that I might be better inclined toward the written word.

Many of my classmates had wanted to be Writers, but not me. I gravitated toward Art, but I was better at talking about it than making it. I had, as my lawyer dad liked to insist with no small hint of pride, a gift for bullshit: a talent for writing with a lowercase w, the same talent he used to compose legal documents on a Dictaphone for transcription by his secretary. I could put together a decent sentence that was easy on the eyes and funneled smoothly into the ears.

When I took the job at the museum, coveted by so many aspiring curators—one of whom, upon finding out I’d gotten the gig, burst into tears in the ladies room at the Midtown public art nonprofit where we were both unpaid interns—I’d just wanted, I guess, a job it would make sense for someone with a degree in “Art-Semiotics” to have. I knew being any kind of assistant would involve a lot of scut work and not much creativity, but it was New York and I couldn’t be choosy. I was lucky to even exist.

I thought I’d be a ghost who brought people coffee, who took notes in meetings, who made dinner reservations for my bosses and their famous friends. What I should have known is that I was such a fucking brat that the look on my face when I was asked to do any of these things would either get me fired or, as it happened, get my bosses to hire another more competent curatorial assistant so that I could be used to spend the bulk of my time ghostwriting their catalogue essays.

Ok, maybe not the bulk of my time, since I did spend a good deal of time taking phone calls from gallery assistants and art critics, formatting wall labels, flirting with whichever masculinist installation artist swaggered into the office that day, attending chaotic meetings where we discussed the museum’s lack of fire insurance (the building was an old public school basically built out of matchsticks), cleaning K.’s ketchup-encrusted desk, and sorting through his invitations to parties and openings to make sure I didn’t miss the odd note from Spike Jonze, Hedi Slimane, Kim Cattrall, or any other target of his sycophancy.

“You don’t have a poker face,” B. remarked one day with his trademark snideness, observing my twisted expression upon being given an undesirable task to perform. I don’t remember what I’d been asked to do, but B. clocked me because he didn’t have a poker face either, and lack of game recognizes lack of game. B. was a brilliant curator and an even more brilliant writer. He would have never, ever let anyone else write for him. He once got so angry with K. that he sent him a dozen emails in succession, each reading, “K. is a fake, phony curator, fuck you.” He called me early the next morning knowing that I was the only person who ever actually checked K.’s email and asked me to delete them all. Of course I did. It was our secret.

When I wasn’t deleting emails or walking around looking like I’d just sucked on a lemon, I was writing. My facial expression didn’t matter, because a ghostwriter doesn’t have a face. I wrote on Sieverding for A. I wrote on Warhol’s screen tests for K.—a catalogue essay for an exhibition mounted at MoMA. I wrote A.’s introduction to the catalogue for Greater New York 2005, a massive museum-wide group show. I wrote other things that weren’t essays—recommendation letters, emails, thank-you notes. There’s a lot that I wrote that I don’t recall having written. There’s no record. My face was probably screwed up all the while, as it tends to be when I’m writing. No one saw it.

I used to tell myself that I would eventually author an art world version of The Devil Wears Prada based on my time at the museum. I told myself I had to start taking detailed notes, that I would forget it all if I didn’t write it down. I never wrote any of it down. My contribution to the chick lit canon remains a fantasy. Even a chick lit author has a nom de plume. A ghostwriter isn’t an author. A ghostwriter doesn’t have a name.

Confusingly for me, my name does appear on some of the shorter essays in Greater New York 2005. After I’d already written the introduction as A., she and the curators realized that there were simply too many artists in the exhibition, and thus too many essays in the catalogue, for a tiny group of people to have feasibly authored. A decision was made to allow curatorial assistants to write on individual artists, provided this didn’t interfere with any ghostwriting they (I) may or may not have also been doing. K. was, I remember, particularly vexed by my newfound authorship. It was as if an act of fission were taking place. He couldn’t stand the formation of a separate entity. Really, he couldn’t stomach the word made flesh. The instrument singing its own little song.

Twenty years later, I write under my own name. I recently added my middle name to my publication name, because there is another media writer named Sarah Kessler who’s written much more, and far more compellingly, about contemporary culture than I have up to this point. I guess I’m a Writer now (though of course my literary friends would call me a writer at best). But I no longer care about that. Most of the time when I’m writing I feel like someone else is composing for me, like I’m a human typewriter. I’ve never not felt this way about what I do. It’s easiest when you don’t think. Let the ghost guide your fingers.

I don’t know if A. publishes anymore, but K. is still out there authoring catalogue essays. I can’t find any of them online. I can’t find any of the essays I wrote for A. or K. either. That’s probably a good thing, because I know I’d be deeply humiliated by my own past ghostwriting. Then again, I didn’t author those essays, so I’d have no reason to feel ashamed.

I’m sure K.’s current catalogue essays are also deeply humiliating. I’m sure he uses ChatGPT to write them. Actually, I’m sure he has an assistant use ChatGPT to write them. A ghostwriter for the ghostwriter. A ghost in the museum for the ghost in the machine.