Beam Ends

How whaling history lives on in Nantucket’s energy politics

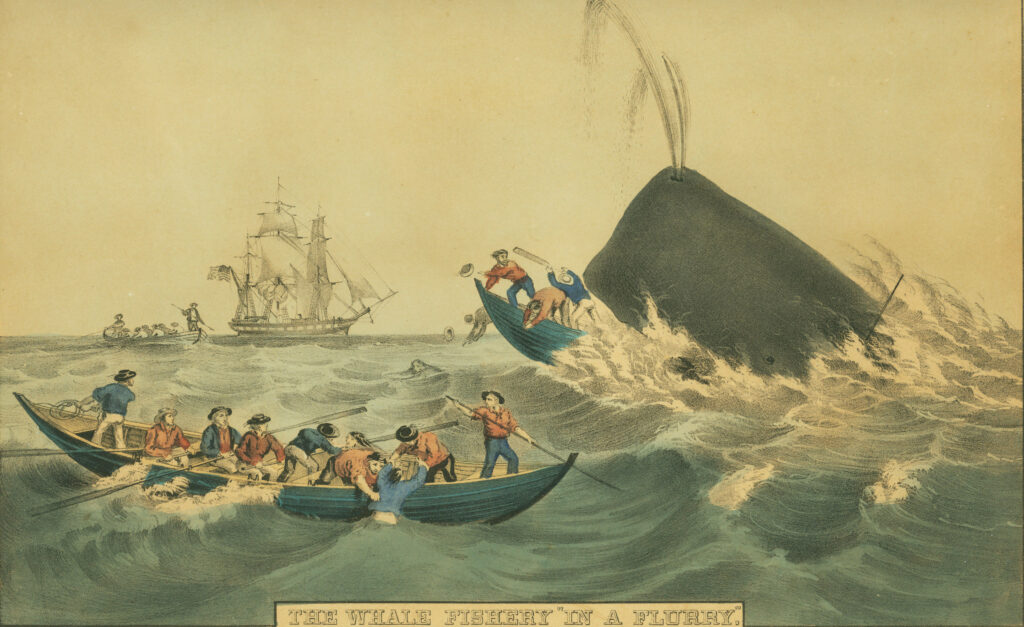

Two centuries ago, Nantucket was a major producer of whale oil, the proto-energy resource that illuminated Great Britain and the young United States. After commercial whalers serially depleted whale populations close to shore, they had to venture farther afield. By the early 1800s, Nantucketers were leaving the island in whaling ships bound for the Pacific Ocean, returning years later with hulls full of oil. The US market for whale oil continued to grow along with the settler nation until the 1860s, when petroleum from the Pennsylvania oil boom pushed whale oil out of the market.

Today, Nantucketers profit from other big businesses, such as residential real estate and tourism. And where workers once prayed for the sight of spouting whales on the horizon, some Nantucketers are trying to halt another energy industry bursting into their view: offshore wind power. The offshore wind farm Vineyard Wind is currently being built in the waters south of Nantucket. When completed, it is expected to supply the grid with enough electricity to power four hundred thousand homes.1 Vineyard Wind is still growing, its turbines rising in sight of Nantucket’s south shore beaches. There she blows.

While protesters decry the wind farm’s proximity to the island, Nantucket’s obsolete whaling industry still haunts public life. Whales are the main feature of Nantucket’s vernacular design and style. A spouting sperm whale adorns the Nantucket town seal. The local brewery’s signature beer is Whale’s Tale Pale Ale. Nantucket is an epicenter of Ivy style, famous for the salmon-colored go-to-hell pants known as Nantucket Reds. The iconic pants are sold exclusively by Murray’s Toggery here in town, and sometimes adorned with embroidered whales. Murray’s even sells whale-pant pants, embroidered with tiny representations of the iconic whale pants.

Whaling on Nantucket has become what Raymond Williams called “residual culture”: a culture of the past that remains an active and “effective element of the present.”2 The uncanny return of whaling heritage in present-day Nantucket demonstrates just how powerfully obsolete technologies and dead industries can shape local economies and environmental practices. Residual culture is one of the ways that obsolete things persist. It is also an underappreciated feature of energy transition.3

“Energy transition” is a deceptive term. The history of energy is not a neat procession of different energy regimes, but a messy entanglement of resources and infrastructures that never really go away. The whale oil industry was brought to its end by a successor oil, petroleum. But as a residual energy culture, whaling performed cultural work in the early days of fossil fuel modernity, shaping the labor and infrastructure of petroleum extraction as well as the terms by which Americans understood modernity. And whaling is still at work on Nantucket today.

“Nantucket’s relationship with whaling shows obsolescence to be a process of partial persistence and selective memory.”

Nantucket’s relationship with whaling shows obsolescence to be a process of partial persistence and selective memory. Commercial whaling in Nantucket is a case study in extractive capitalism. It produced wealth for a few, but labor exploitation for most. Its annals contain the familiar fare of environmental degradation, imperial expansion, industrialization, and rough economic cycles of boom and bust. Some of the foremost whaling historians in the world steward the presentation of this bloody industrial history at the Nantucket Historical Association and its flagship Whaling Museum. But Nantucket’s charm can lull visitors and locals alike into simpler, more selective historical understandings, which conveniently offshore extractive violence when explaining the island’s wealth.

These selective renderings of history invite the island’s visitors and residents to imagine that Nantucket’s present-day conspicuous wealth has a deep history reaching back to the whaling days. Weathered shingles make manicured historical houses and new mega-mansions just quaint enough: they refer to that nineteenth-century past without making anyone think about extractive violence. The luxury landscape also hides the fact that whaling wealth left Nantucket in the mid-nineteenth century, leaving houses derelict and residents impoverished for decades, before summer tourism emerged as the key industry it is today. The island’s current prosperity owes much to part-time summer residents who bring considerable wealth with them.

The median sale price for a home on Nantucket hovers around $3 million. The record for the island’s most expensive residential real estate was broken last summer, when the 3.5-acre waterfront estate called Beam Ends sold for $38 million. Whaling history is written—often apocryphally—into real estate listings for such summer mansions. The real estate agent who sold Beam Ends told the local news outlet, the Nantucket Current, about the property’s connection to whaling history: “The purchasers are an old New England family who we feel will be respectful stewards of the property and appreciate its history which included ownership by a whaling captain a century and a half ago.”4 The main house at Beam Ends was built in 2008.

The debate over offshore wind power on this tony island does not fall exactly into familiar NIMBY protocols. Offshore wind generally divides people along political party lines. Many on the left support offshore wind development because wind is a renewable energy resource that will lessen dependence on fossil fuels and mitigate the damages of climate change. Those on the right tend to oppose climate change mitigation in favor of protecting fossil fuel jobs, infrastructure, and financial interests. Wealthy liberals have also historically opposed offshore wind turbines sited too close to their properties. But this time, offshore wind opponents on Nantucket and elsewhere are attempting to stop turbine construction on behalf of—you guessed it—whales.

On Nantucket, a group called ACK4Whales is attempting to halt offshore wind development on the grounds that wind turbines endanger whales. (ACK is the island’s airport code and a popular insider shorthand for the island.) ACK4Whales is focused on threats to critically endangered North Atlantic right whales, which feed off the coast of New England. The group raises valid concerns about how a massive offshore infrastructure project will—at best—interrupt the lives of whales. But there are reasons to wonder how much offshore wind opponents actually care about whales. Protecting these marine giants should also surely mean caring about climate change, ocean acidification, ship strikes, and the offshore oil and gas infrastructures that are also, demonstrably, very bad for whales. But this latest phase of the “save the whales” campaign is focused very narrowly on the offshore wind threat.

Nantucketers are not the only people protesting wind power on behalf of whales. Offshore wind’s threat to whales has made its way into regional and national right-wing political rhetoric. Even Donald Trump has weighed in, claiming that offshore wind turbines “drive whales crazy.”5 Some believe that protest groups like ACK4Whales have not been organized at the grassroots level, but have instead been fabricated and astroturfed by distant right-wing groups interested in preserving the hegemony of fossil fuels.6 On its website and Facebook group, members of the ACK4Whales network deny connections to fossil fuel interest groups and point out—rightly—that offshore wind companies are themselves enmeshed in fossil fuel interests.

Marine scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration state that there is no evidence that offshore wind causes whale deaths.7 According to NOAA, the biggest threats to large whales are vessel strikes, entanglement in fishing gear, and climate change. Recently, NOAA proposed to Congress a rule that would, according to its scientists, actually protect North Atlantic right whales: a speed limit requiring boats larger than thirty-five feet to reduce their speed to ten knots during critical times in the right whale’s migration.8 Commercial and sport fishermen, ferry operators, freight companies, town governments, and tourism industry leaders all along the East Coast are raising the alarm, claiming that the rule would devastate their businesses. The speed reduction proposal has made strange bedfellows of groups who are otherwise fighting one another on the issue of offshore wind.

On Nantucket, it might be too late for opponents of offshore wind to halt turbine production. During the permitting and public input process over four years ago, wind power developers struck a good neighbor agreement with the government of Nantucket and local heritage nonprofits.9 During those negotiations, it was not whale welfare but Nantucket’s whaling heritage that steered conversations about offshore wind. At that time, the negotiating partners tried to determine whether the wind turbines would have an adverse visual impact on Nantucket and thereby endanger its National Landmark status. The island claimed this status owing to its unique whaling heritage and its unbroken sea view, which planners call the “viewshed.”

In 2024, I interviewed Mary Bergman, the executive director of the Nantucket Preservation Trust and one of the signatories to that good neighbor agreement. In compelling terms, she explained to me how climate change represents the biggest threat to Nantucket’s heritage. “If we don’t have an island because it’s eroding into the sea, because the sea levels are rising, there’s nothing to preserve. [Climate change is] a bigger threat to the landmark than seeing windmills on the horizon.” The Nantucket Preservation Trust has created a Resilience Toolkit to help islanders deal with the imminent dangers of climate change. Bergman also brings a deep and complex understanding of Nantucket’s history to debates about offshore wind. I asked her to think about why the blank ocean horizon has become a resource in need of protection. She said that it has to do with the idea of isolation, which is “integral to the way that Nantucketers think about themselves today.”

It takes an enormous amount of energy, fossil-fueled and otherwise, to keep Nantucket feeling isolated: fuel for ferries, yachts, and ever-larger private jets; gas for the big four-wheel-drive vehicles required to navigate the island’s unpaved roads; umbilical undersea power cables connecting the remote island with the grid. Intensive energy consumption makes it possible to enjoy wealth while remaining isolated from its origins or consequences—to wear whale pants without thinking too hard about harpoons.

Isolation is a myth in the age of climate change—particularly when whales, Nantucketers, and all the rest of us on the planet confront existential threats and our own implications in them. Herman Melville, that great chronicler of Nantucket whaling, disputed an earlier myth of isolation almost two centuries ago: “They were nearly all Islanders in the Pequod, Isolatoes too, I call such, not acknowledging the common continent of men, but each Isolato living on a separate continent of his own. Yet now, federated along one keel, what a set these Isolatoes were!”10 We, on Nantucket and off-island, too, are a set. Climate change federates us. It is ironic that last summer’s real estate blockbuster is called Beam Ends, because to be on “beam ends,” in nautical parlance, is to be in dire circumstances, blown over, helpless. In the age of climate change, we are all at beam ends—and confederated along one keel. ■

- Stanley Reed and Ivan Penn, “A Giant Wind Farm Is Taking Root Off Massachusetts,” New York Times, June 28, 2023. ↩︎

- Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature (Oxford University Press, 1977), 122. ↩︎

- Jamie L. Jones, Rendered Obsolete: Energy Culture and the Afterlife of U.S. Whaling (University of North Carolina Press, 2023). ↩︎

- Bruce Percelay, “$38 Million Sale of Monomoy Home Breaks Island Record,” Nantucket Current, June 30, 2023. ↩︎

- Lisa Friedman, “No, Wind Farms Aren’t ‘Driving Whales Crazy,’” New York Times, February 16, 2024; Molly Taft, “The Latest Culture War Starts with Dead Whales,” New Republic, November 15, 2023. ↩︎

- Molly Taft, “The Latest Culture War Starts with Dead Whales,” New Republic, November 15, 2023; Climate Nexus, “Offshore Wind and Whales,” Climate Nexus blog, January 2024. ↩︎

- NOAA Fisheries, “Frequent Questions—Offshore Wind and Whales,” NOAA Fisheries blog, June 1, 2024. ↩︎

- Michelle Gustafson, “A Boat Speed Limit Is Pitting Yacht Owners against Whale Lovers,” Wall Street Journal, March 14, 2024; John Carl McGrady, “‘Devestating’ Speed Restriction Proposal Gains Momentum in D.C., Prompting Alarm on Nantucket,” Nantucket Current, May 23, 2024. ↩︎

- Nantucket Parties, “Good Neighbor Agreement,” Government of Nantucket website, accessed August 24, 2024. ↩︎

- Herman Melville, Moby-Dick (1851), Third Norton Critical Edition, ed. Hershel Parker (W. W. Norton, 2018), 101. ↩︎