Data and the Dybbuk

The chatbot confidently misreads the history of the Yiddish theater

Over generations, my family has been haunted by its ambivalent relationship to Judaism. We are culturally Jewish, but not in any organized religious or institutional sense. That being said, my grandparents spoke Yiddish at home and always had a mezuzah mounted at their door—a small encased scroll containing verses from the Torah that is both a reminder of a covenant with God and a signal to the world that this is a Jewish household.

Growing up, I would hear vague tales of an illegitimate liaison: my great-great-grandmother, Dora Burstein, left the old country and “ran off” with a man who was not the biological father of her first child, my great-grandfather, Theodore. It all sounded rather theatrical. Perhaps implausible. That is, until Yiddish theater began to provide some clues to our family’s lost history.

A family portrait of Dora, Dr. Snitzer, Theodore, and half-sister. PHOTO COURTESY OF TAMARA KNEESE.

Here’s what we knew before the curtain began to be lifted: little Theodore came to New York from Lithuania when he was six. Dora, his mother, had had him when she was just thirteen, and the man she came over on the boat with, Jacob, was not Theodore’s father. Dora, they say, was a bit of a wild woman, a poet, and a drunk. Theodore learned the family trade, became an optometrist like his parents, and took a Jewish wife at the age of sixteen. But his son, my grandfather, distanced himself from Brooklyn and from Jewish tradition, and moved to Virginia to pursue a PhD in classical archaeology while passing as a redheaded gentile (though he would later marry Leah Goldberg, a distinctly Jewish personality).

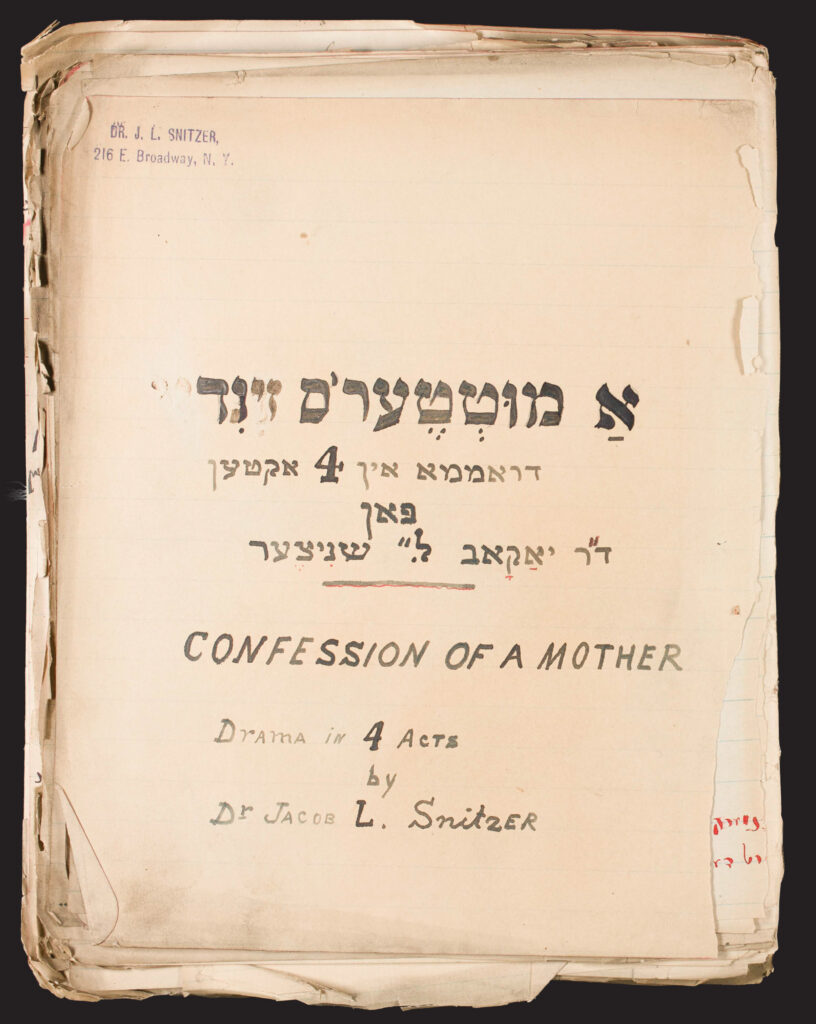

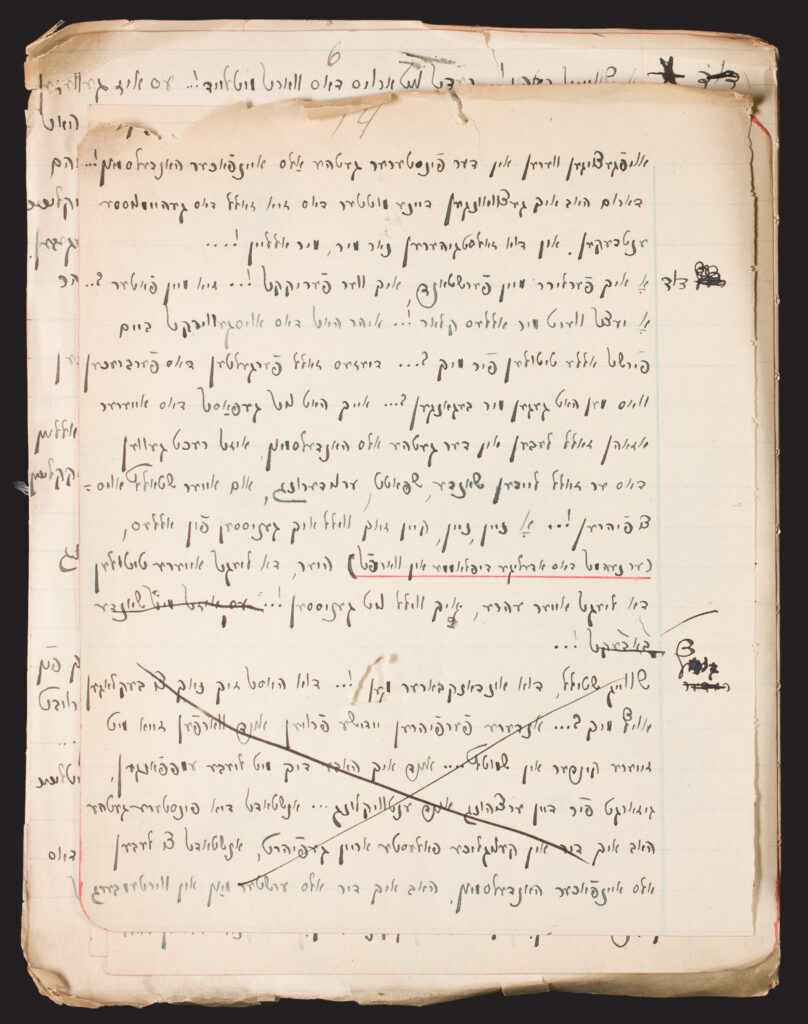

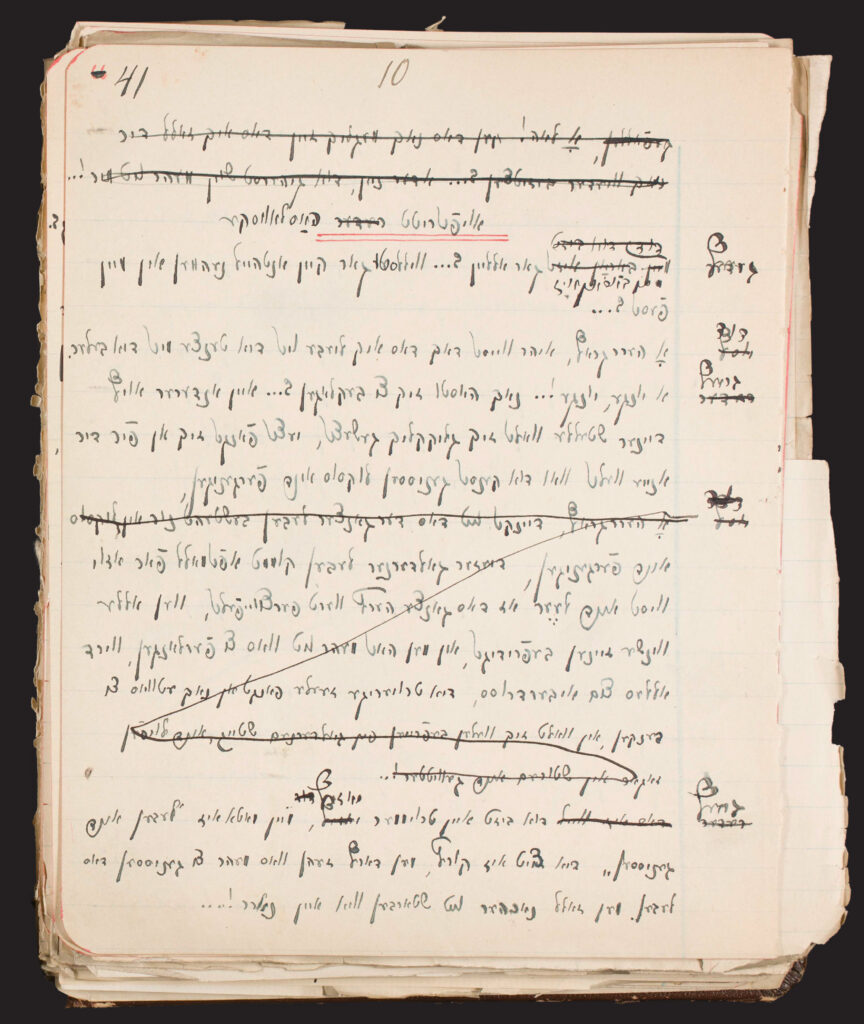

It was only after my grandfather’s death that we discovered the Yiddish plays and other materials written by his step-grandfather and grandmother in an archive at the Center for Jewish History in New York. I found the archive online when I was searching for the location of the family’s long-defunct optometry practice. For several generations, no one in the family had any idea that Dora and her husband, Dr. Jacob Lazarus Snitzer, had been part of the Yiddish theater scene. There were papers, letters, and manuscripts (including theater contracts signed by Jacob Adler, the renowned Yiddish theater mogul), all available for us to translate and read.

These were compelling through-lines—my mother is an actor, and my father is a playwright who has even staged plays on the Lower East Side, close to where Jacob and Dora staged theirs. We also learned that Dora’s father and brother were rabbis, another detail missing from our family history. In a biographical note for Jacob on the archive’s website, Jacob and Dora were listed as having five children.1 Theodore, my great-grandfather, however, was missing. There was no trace of him or his progeny. He had become a ghost.

There are other ghostly figures that haunt the Yiddish stage. In Jewish folklore, a dybbuk is a wanderer that takes hold of people’s bodies, forced into a liminal position because of sins committed during life. Dybbuks have long had a media presence, from the Yiddish theater to TikTok.2 They became popularized by a play that was written in Russian during World War I, performed in Yiddish in 1920, and staged in English in New York in 1925.3 In 1937, a popular Polish film adaptation was released. Fast-forward to the COVID-19 pandemic and one could find Jewish organizations hosting online performances of The Dybbuk via Zoom.4 Through these iterations, the dybbuk became a cultural phenomenon, a site of translation across time periods, geographies, and languages—and as theatrical dybbuks connected far-flung diasporic communities, real dybbuks assumed more familial forms.5

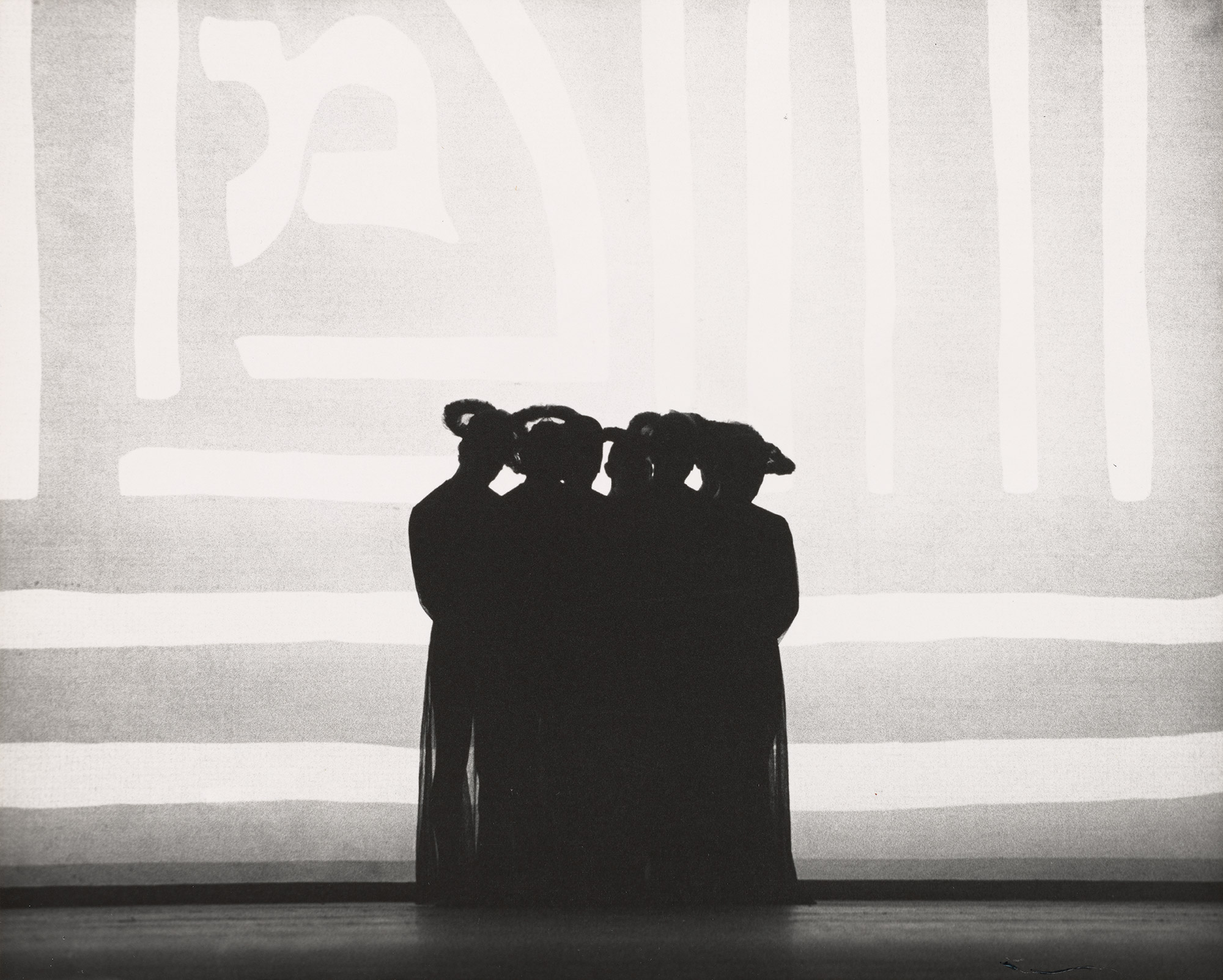

A dybbuk possesses a woman in a stage production of The Dybbuk, 1925. “MARY ELLIS [RIGHT] AND UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD PLAYHOUSE STAGE PRODUCTION THE DYBBUK.” THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY DIGITAL COLLECTIONS, BILLY ROSE THEATRE DIVISION

Within the figure of the dybbuk, elements of the dead and the living comingle, bridging the old world and the new. As with spirit possessions in many other folkloric traditions, dybbuks tend to inhabit the bodies of women. This was the case in my own family, where Dora herself has taken on the role of dybbuk: returning, wandering, blurring. My brother claims he saw Dora’s ghost when he was a child. He saw a petite woman with red hair like my mother’s, but he realized her dress looked out of fashion, like it was from another era. Dora had returned, both doubling my mother and collapsing the boundaries between past and present.

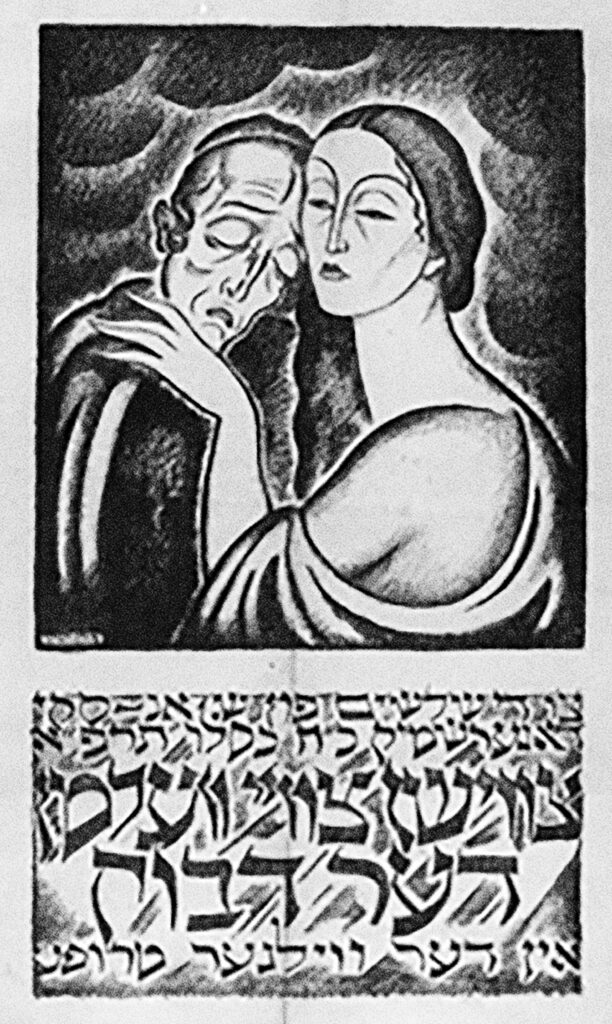

1920 Yiddish-language advertisement for an early production of The Dybbuk by the Vilna Troupe. WIKIMEDIA COMMONS.

These ghostly conjunctions of family lore and Yiddish theater began to raise questions for me and my brother. While most of my scholarship is critical of AI, and I avoid using it in my personal and professional life, my brother regularly uses ChatGPT as an interlocutor. In search of answers, I asked him to consult ChatGPT to tell us who Theodore’s real father was, why he was so cut off from the rest of his family and from his Jewish roots, and why he had vanished from the archived biography.

But we didn’t stop there. We asked ChatGPT to help us meet the dybbuk herself, Dora, as well as her son, our disappeared ancestor, Theodore. My brother’s prompt conjured a simulation of Dora:

[Dora, the weight of memory settling in her voice like dust on old letters] Oy, Tataleh … There are things lost, not because they were unimportant, but because the world we came from was chaos. Records? We didn’t have records. We had stories whispered in candlelight, names etched in our hearts, not on papers.

This is both funny and ironically incorrect, given the strong literary tradition of Lithuanian Jews, who very likely were keeping meticulous records.

ChatGPT went on to state, in Dora’s supposed voice, that Theodore is missing from the family archive because no “scribe” followed them from Russia, and that his father was a shoemaker named Yankel. None of this is remotely accurate, of course—ChatGPT hallucinates and extrapolates to fill in gaps. It is not a truth-teller or a spirit medium. It is a tool that regurgitates the host of Yiddish theater tropes it consumed as training data. The theatrical tradition of The Dybbuk here was crossing over to inform the digital incarnation of our family dybbuk, Dora. Strange, but telling.

While the logic of generative AI is built on the premise that more data will yield more accurate, lifelike outputs, the dybbuk remains elusive. It is more than the sum of its inputs. A dybbuk is weighed down by the traumas of history; it is a manifestation of unfinished business and unresolved conflict. Wild-woman Dora could never be pinned down by the endless data-tumbling of ChatGPT’s archive.

AI has become an object onto which people project their greatest hopes and fears. It promises eternal life by uploading a person’s consciousness into a computer, at the same time as it poses an existential risk to humanity, with some technologists waiting for the day when the robot overlords will kill us all. Much of my scholarship over the past decade and a half has considered the relationship between an individual’s corpus of data (creative outputs across and after a lifetime) and the tech companies that attempt to monetize, control, govern, and steward these sacred digital remains.6 In the current hype cycle associated with generative AI, the technology is imagined as filling in for other forms of human companionship and intellectual or creative labor, acting as a lover, a therapist, an artist, a teacher, and a doctor. Generative AI’s malleability, the way it can switch applications and contexts, and its capacity for hyperpersonalization also lend it a ghostly quality, as when ChatGPT is used to bring historical figures back to life as an educational tool, instead of having students visit an archive or read history.

Despite my Luddite sensibilities and critiques of generative AI, I do find myself somewhat disappointed that ChatGPT couldn’t fake it a little better. But, chasing Dora the dybbuk, I can appreciate the desire to find meaning in the messages of the stochastic parrot that is AI.

Niche startup companies claim that chatbots can mimic a conversation with a dead loved one to help us overcome grief. According to companies like Google, large language models (LLMs) can, moreover, work as translators, filling in gaps in the linguistic record available on the open web and bolstering Indigenous languages. LLMs are built on vast stores of data, including those of the dead, as content from social media platforms, academic books, and other creative works are taken up and Frankensteined together as a golem of prose. But despite some seemingly spiritual or noble qualities, there is so much that AI cannot tell us. AI creations often take on the shape of something real, stated confidently in a ghostwritten voice reminiscent of the Yiddish stage. What do we do when the content is all wrong, even monstrous?

AI might have failed to bring Dora back, but part of me wondered if the archive—the plays and other manuscripts themselves—might reveal part of the story. Maybe there would be clues about Theodore’s birth. I read the English translation of Jacob’s novel, The Story of the Baal Shem: Life, Love and Teachings of the Founder of Chassidism and Jewish Mysticism, and was surprised to see that one of the book’s major themes was the kidnapping and rape of Jewish girls by non-Jewish men, and the harshness of Jewish law toward illegitimate children. There is even a dybbuk in the story. A miller’s daughter is possessed by the soul of an illegitimate boy she had once loved and had been forbidden from marrying. Dybbuks materialize when a secret needs to come to the surface.

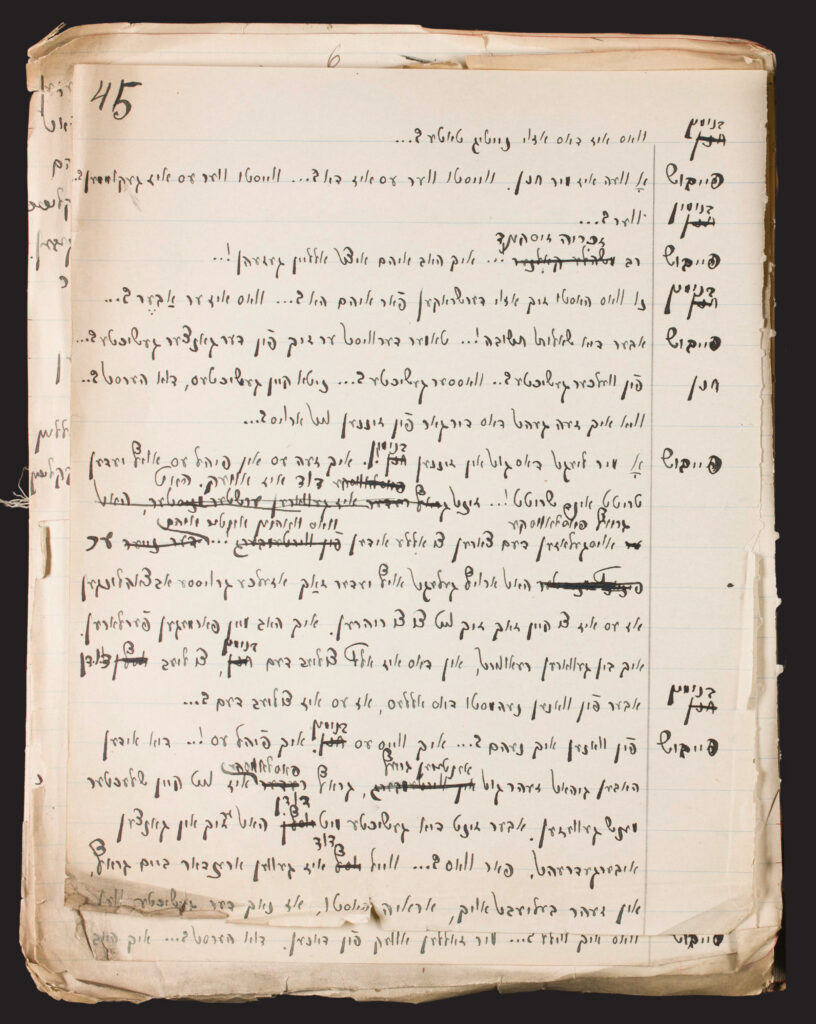

One of the plays also at the archive is titled Confessions of a Mother or, alternatively, A Mother’s Sin. Intrigued by this title, my own mother hired a translator so we could see if there were any clues suggesting why Theodore had been left out of the family’s genealogy. The play centers around a man whose patrilineage is in question. As it turns out, he’s the illegitimate son of a German count and that’s why he can’t marry his beloved, who is the daughter of a rabbi. The translator left notes for us, pointing out that the play was clearly a work in progress, that characters kept changing names, that various parts were crossed out, that different handwriting indicated at least two authors, and that the entire third act of the play was missing. Embedded in the translated text is her aside to us, the readers: “A very different hand—messier, with a lighter pencil, for the next few pages. I will do what I can …”

In a strange twist, the human translation of the play mirrors some of the pitfalls of ChatGPT’s rendering of Dora’s story. At times, the translator’s interjections reveal her exasperation with the changing names and convoluted story. The writing style and character development, indeed, leave much to be desired. The play is unfinished, trailing off in parts. It doesn’t make for clean data. Apparently, it included lines that the translator remembered from somewhere else, perhaps lifted from another schlocky play. Yiddish phrases like “Oy vey iz mir” are sprinkled awkwardly throughout. There is a song that is referred to but not written down.

The translator told my mother that the specific Litvish dialect was hard to parse, and that there were arcane Talmudic references that we would need a Talmudic scholar to explain. (This is why you pay people to translate work instead of relying on AI to do the job.) And while we suspect that Dora was responsible for the different handwriting in the text (she was also a playwright after all—not just an optometrist, poet, drunk, etc.), we will never have a real answer. And therein lies the rub.

As much as general-purpose AI technologies promise a fast, confident answer to any question, they fall short. The dybbuk, by contrast, has remained a lasting figure precisely because of its liminal status, precisely because it cannot be pinned down as the proverbial sum of its parts. Like the difficulty of translation across time and space, the dybbuk’s power lies in its indecipherability.

- https://archives.cjh.org/repositories/3/resources/15655 ↩︎

- https://www.inverse.com/input/features/dybbuk-box-dibbuk-kevin-mannis-zak-bagans-haunted-hoax-revealed ↩︎

- https://forward.com/culture/134450/sympathy-for-the-dybbuk/ ↩︎

- https://thetheatretimes.com/digital-ghost/ ↩︎

- https://vilnacollections.yivo.org/This-is-What-Researchers-Dream-About-Finding-A-Fragment-About-The-Dybbuk ↩︎

- Tamara Kneese, Death Glitch: How Techno-Solutionism Fails Us in This Life and Beyond (Yale University Press, 2023). ↩︎