The Extortion Stack

This Has Been an Unauthorized Cybernetic Announcement

Start with an archetypal story: a single brave hacker with phenomenal technical chops liberates the suppressed information, and with it society as a whole. “More bits are being added automatically as it works its way to places I never dared guess existed,” says the hacker of his epic exfiltration program (Brunner 1995:251). “In other words, there are no more secrets.” He will bring down every rotten institution, expose every lie, open government to the governed. “As of today, whatever you want to know, provided it’s in the data-net, you can now know.” (Brunner 1995:248) He will launch the leak to end all leaks, one that will not only overturn but replace the government itself.

All this is from John Brunner’s 1975 science fiction novel The Shockwave Rider. Set in the early 21st century, the book imagines a state-corporate surveillance and identity-management system and a hopelessly distracted and media-saturated population of flexible tech and service industry workers unable to think about anything in the long term. These days, it barely qualifies as fiction; it’s a lot more prescient than anything involving a lunar base. His protagonist—intelligent, brilliant, but also isolated and consumed by an identity crisis and suicidal impulses—makes him instantly recognizable as drawn from real-life figures like Len Sassaman (a privacy advocate and systems engineer who tragically committed suicide in 2011) and fictional representations like Elliot Alderson, the anxiety-afflicted main character in the TV hacker drama Mr. Robot. Even the liberating hack Brunner postulates is not too improbable in the centralized data apparatus he envisions: later computer scientists adopted his term for “worm programs”—or just worms—incorporating networked machines into a larger distributed computation (Shoch and Hupp 1982). There is one glaring fantasy element in this story, though, one giant fire-breathing dragon on what could otherwise pass as the 21st-century city skyline: what happens after the leak.

First, the data that are found and distributed are clear and unambiguous. Here, there are no fundraising dinners that may or may not correspond to political influence, no unethical behavior that would need witness testimony to corroborate, no fog of war. The data are a picture of evil. Second, and far more improbable than the mega-hack itself, all the data are delivered by the worm program in plain, polemical English, linked to the outrage in question (the protagonist’s program has also infiltrated all publishing tools): a corporate report comes with documentation of fraud, canned food is labeled with all the dangers to health it contains, a cosmetic product is accompanied by its known carcinogens and a history of legal cover-ups. “This is a cybernetic datum derived from records not intended for publication,” the notes say. “This has been an unauthorized cybernetic announcement.” (Brunner 1995:245) If you ask the worm system about a politician or a scandal, it returns a cogent summary of precise and documented malfeasance in the style of an investigative journalist. Finally, this leak to end all leaks provokes the population to rational and exactly targeted outrage. Everyone investigates and discusses and sorts through the worm’s data and dismantles the existing society. In its place, using hidden economic data found by the worm, they build a kind of cybernetic communism, ruled by distributive algorithms and total informational transparency: “Therefore none shall henceforth gain illicit advantage by reason of the fact that we together know more than one of us can know.” (Brunner 1995:280)

Of course actual leaks don’t play out like this. Even the Pentagon Papers, which would seem like a model for The Shockwave Rider, required an enormous amount of informational labor to organize, shape, and explain, both by Ellsberg and by Woodward and Bernstein (Ellsberg 2003). Gigabytes of data taken from enterprise resource planning software do not return one-click results of “fraud” or “not fraud.” (Forensic accounting is a multicredential career for a reason.) The WikiLeaks “Collateral Murder” video was exceptional precisely because it was an unambiguous video of a battlefield killing, and even that was edited and framed with text. The most recent WikiLeaks releases, as of this writing, seem heavily redacted and organized to put the Clinton campaign in the worst possible light. (Pick some choice invective out of thousands of messages, set it in Courier typewriter font so it looks more “official,” highlight a couple random passages, and you too can stun the world with your revelations.) The Guardians of Peace hack, which released material from Sony Pictures Entertainment, turned up a few things seeming to demand public action (lobbying efforts to coerce internet service providers [ISPs] into blocking sites and traffic) but mostly offered a salacious opportunity to read the correspondence of executives being awful to each other on their iPads. It also exposed the data of thousands of innocent people. If we count doxes (the public release of identifying information for online identities) as leaks, then the work of leaking has grown to encompass the lazy man’s death threat: to reveal all the information about someone you dislike, and wait for someone else to call in a fake active shooter and incite a SWAT team raid.

Somewhere along the line, between the 1975 science fiction vision and the realization in the 2010s, a threshold was crossed. Hacking, leaking, and the fantasy of the effects of secret knowledge have taken on a very different cast. I think there are two related components to this change, a cause and a consequence: the volume of data, and the space of available interpretations. (These two components share an interesting symmetry with Gorham’s argument about episteme and doxa—truth and opinion—and the consequence includes the distinct forms of slow and fast leaks described by Adam Fish, both in this issue of Limn.) Broadcast media technology gave us the fantasy of the single decisive leak—“Lonesome” Rhodes unwittingly insulting his public in A Face in the Crowd on a hot mic, or newspapers breaking the mistress story in Citizen Kane—but Podesta-size, Cablegate-size leaks (hundreds of thousands of messages, millions of user accounts) work differently. They speak to the corresponding media fantasy of our time, the daydream of big data: information at the gigabyte scale, millions of rows or nodes, will provide a new insight, unavailable by other means—a social graph of call metadata and CC’d messages exposing a conspiracy, or dissimulation revealed in keyword analysis across an industry.

In practice, though, the increase in quantity by orders of magnitude—combined with immediate and widespread distribution—has not made for bigger truths. Instead, it has enabled more truths…or “truths.” It has expanded the space of available interpretations, analysis, and consequences, from journalistic exposés of internal party discipline advancing Clinton’s candidacy, to a troll-fueled, gun-toting showdown at a pizza place in Washington, DC. To substantiate this argument for the importance of volume and interpretation, I want to challenge it: What if there was one paradigmatic hack-and-leak case where the Shockwave Rider fantasy could really work? What if there was a group who deserved no privacy, with a comically evil company, a lie to be exposed, and a righteous cause where the mega-leak’s information could speak for itself?

I Have a Copy if You Don’t Pay

Avid Life Media was a Toronto-based “leading business in the online dating industry.”[1] (Since the events described here, they’ve rebranded as the lowercase “ruby Corp.”) They ran a slate of remarkably sleazy dating/hookup sites, including Established Men, Cougar Life, Man Crunch (really), and Ashley Madison. This last promised easy and straightforward extramarital affairs, thriving on its scandalous publicity with slogans like “Life is short. Have an affair.”

In fact, the Ashley Madison business model was a 21st-century version of the early pornographic film loops studied by the cinema scholar Linda Williams. She explained that you don’t see representations of orgasm in most of these early porno films because they were screened nickelodeon-style in brothels to arouse the patrons but not satisfy them, so they’d pay for services (Williams 1989:74). They were tantalizing frustration machines. Likewise Ashley Madison: setting up an account was free, but sending messages, giving “virtual gifts” (the usual social network chintz), and initiating instant message sessions all cost “credits,” which users could buy in blocks from $49 to $249 (which came with an “affair guarantee”). In other words, it was bad for the company’s income for users to proceed swiftly to an in-person affair. The optimal arrangement was a closed loop of back-and-forth messaging and flirting that never went anywhere. Luckily for Avid Life Media, Ashley Madison’s userbase included almost no actual women; the company used chatbots instead to sustain endless routines of ELIZA-like flirting with men.[2]

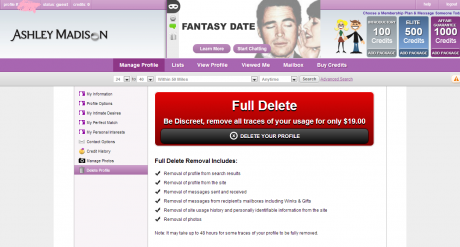

This marvelously depressing but lucrative strategy, where the creepiness of RealDoll porn-chat bots meets the repetitive, inescapable time of Last Year at Marienbad, had a final sting. The frustration machine produced a lot of records: profiles, sexual preferences and fantasies, photos, and messaging and chat transcripts, all linked to a credit card and a single identity. When the customer eventually felt guilt and regret, or fear of discovery, they would shut down their account and be obligated to take advantage of the “Full Delete” option—for only $19—which would entirely delete every record of their activity on Ashley Madison.

Avid Media did not fulfill their end of this final sale. The technical challenges involved in completely removing records like this are considerable, especially on a social network (of sorts) that accepted credit card payments. The Ashley Madison team didn’t bother, instead settling for the appearance of deleted accounts. The user would receive a confirmation message that alluded obliquely to this, stating that the profile “has been successfully permanently hidden from our system”: a run of imprecise weasel words that didn’t add up to the total data destruction one had been led to expect. Nineteen dollars to set “AccountHidden=” to “TRUE” for everyone who ever got drunk in a hotel room, started a free account in a moment of weakness, and regretted it the next day was a fantastic way to make money.

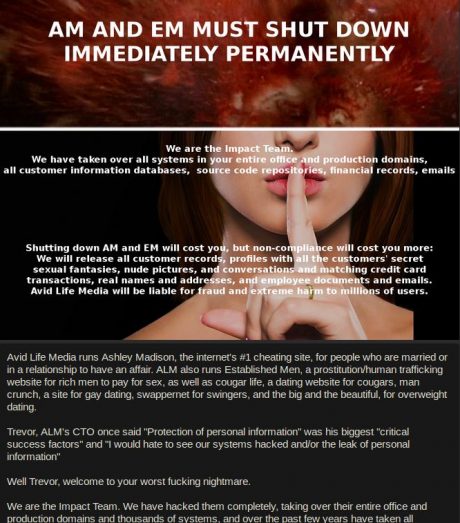

On July 19, 2015, Ashley Madison’s website and internal network displayed a new landing page. Their banner had been the lower half of a woman’s face with her finger to her lips: shhhh (with a wedding band, naturally). The new page completed the upper half of the banner with the gory exploding head from David Cronenberg’s vengeful-telepath movie Scanners, and a demand: “AM AND EM MUST SHUT DOWN IMMEDIATELY PERMANENTLY.” (EM, Established Men, was Avid Life’s “sugar daddy” network, here identified as a “prostitution/human trafficking website.”) “We are the Impact Team. We have taken over all systems in your entire office and production domains, all customer information databases, source code repositories, financial records, emails,” the page began. They were holding Avid Life hostage, demanding not money but the shutdown of the two sites. Their objections against Ashley Madison were based on the failure to deliver on the “Full Delete” promise: “[Avid Life Media] management is bullshit and has made millions of dollars from complete 100% fraud.” But the Impact Team’s strategy was not to release information about the company itself. It was to leak information about the users: “We will release all customer records….” They included 40 megabytes of Ashley Madison data as proof.

Avid Life did not comply. On August 18, the Team released almost 10 gigabytes of data on the so-called “dark web” Tor network; it was indexed and searchable on the open web the next day. The company began issuing Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) takedown requests, the kind of thing normally sent by copyright holders to have movies and music pulled from the web. On August 20, another 19 gigabytes of data were leaked.

Within hours of the data’s release, the first projects allowing the casual browser to easily search the data began to launch. These were front ends for the leak, comparable in outline with the landmark Diary Dig project for searching the leaked data in the Iraq War Diaries. People would enter email addresses, searching for celebrities, politicians, their spouses, bosses, or themselves. Within days, the scams and blackmail began. The scams (some of them products of those search sites) announced that you—which is to say, any email address used as a search—were indeed in the Ashley Madison leak, with all the salacious, marriage-ending, life-ruining information attached to your identity. The scammers promised to really fully delete your information, just in time to save you, for a fee.

The blackmail was far more sophisticated: a ransom strategy, with an email sent to addresses in the database.[3] “I now have ALL your information,” the blackmailer wrote: “I have also used your profile to find your Facebook profile, using this I now have a direct line to get in touch with all your friends and family.” The blackmailer’s system would automatically forward all your Ashley Madison records to your social network (“and perhaps even your employers too?”) unless it received a payment in Bitcoin within 72 hours. Like the false “Full Delete” option, it was a straightforward way to make good money from desperate people. It also marked the final step of something remarkable, read from beginning to end as a linked series of software components: the extortion stack. You could be tempted, tantalized, sign up to betray, betray (in spirit if not in flesh), create evidence, go through guilt and regret and concealment, and finally be shamefully and secretly blackmailed, all without ever interacting with a person, conducted completely by software: entrapment as a service.

The blackmailers also provided thoughtful advice on how to update your Facebook privacy settings to head off their competitors, but of course, “I have a copy if you don’t pay.” Or rather, the system has a copy, and will pull the trigger if the ransom isn’t paid. The whole process was automated (or claimed to be): this had been an unauthorized cybernetic announcement.

We Will Release All Customer Records

If you step far enough back and let the details blur, these stories from 1975 and 2015 have a lot in common as heroic tales of hacking. Anonymous hackers completely compromise an evil corporation, exfiltrate and collate all their data, hold them to account, and then release all to the public. They reveal fraud and hypocrisy in all corners of society, with a combination of general dumps and targeted disclosure. They destroy their target, more or less. As we selectively bring details forward, the story becomes even more canonically a tale of hacker glory: they open-source a vast tranche of records of misdeeds, for which others provide friendly user interfaces and crowd-sourced analysis, sidestepping legal challenges with mirrors and torrents of the data (information wants to be free, man), automating repetitive tasks and making use of tools like Tor and Bitcoin.

“Evil” isn’t really the right word for Avid Life Media, though: their online properties were tawdry and exploitative, and at least one of their promises was straightforwardly fraudulent, but they’re small fry compared with Wells Fargo or Dow Chemical. In practice, Ashley Madison was in the business of preventing actual extramarital affairs, diverting those impulses into expensive, go-nowhere flirty chats with crude software. (It would have been much easier to break your vows with the help of Craigslist or Grindr.) Their userbase is easy to mock and deride, but the data carry no context, no human nuance: accounts could be made as pranks on friends or coworkers, or from a benign curiosity about a notorious site often in the news, or for reasons, unpleasant as they may be, that are no one else’s business. “We will release all customer records,” said the Impact Team’s landing page demand. “Avid Life Media will be liable for fraud and extreme harm to millions of users.” If Avid Media did not comply, therefore, and possibly even if they did, it would prove necessary for millions of users to come to harm. Their marriages, careers, and public lives would have to be imperiled and rendered vulnerable to blackmailers and extortionists to bring the adversary down. And so it proved indeed.

Set aside the question of good or bad intentions on the part of users, Avid Life Media’s executives and developers, the Impact Team, and those making use of the leak after the fact (journalists and blackmailers alike). The sheer volume of leaked data dwarfs intentions. It was used to expose the hypocrisy of religious media figures, to provide trenchant evidence of a company’s fraudulent behavior, to ruin the lives of random individuals, to threaten personal revenge on particular attorneys in the Department of Justice, and to build a blackmail machine. This was the threshold crossed between 1975 and 2015, to return to the argument: not just that of white hat/black hat, or private individual/state agency, or corporation/country, but the volume of data that could be found, released, and easily explored by amateurs, and with it the space of available interpretations.

To its contemporary reader, The Shockwave Rider‘s most improbable element might have been a computerized society running over phone networks, or the immense consolidated power of transnational tech companies. Looking back, the fantastic element is that all the data in the single mega-leak was so perfectly legible in its meaning. The public knew precisely what it meant, which is to say that all of it meant only one thing: an arrow pointing to a better government. Did the Impact Team want to destroy Avid Life Media for their fraudulent behavior, to punish cheaters, to amuse themselves, or all of the above? It doesn’t matter. Writers, journalists, extortionists, scammers, spouses, and opposition researchers all made their own interpretative uses of the leak, as they and others have interpreted the mass of data of other mega-leaks. “As of today, whatever you want to know, provided it’s in the data-net, you can now know”: Brunner’s promise contains its own latent disaster in that unspecified, second-person you.