The Thick and Thin of the Zone

Several years into a major political transition in Myanmar, the Thilawa special economic zone (SEZ) officially opened for business in September 2015. Located on a riverbank 14 miles southeast of Yangon, Myanmar’s largest city and former capital, the Thilawa zone is a joint venture between Myanmar and Japan. In an opening ceremony short on neither pomp nor pageantry, hundreds of business executives and politicians clustered beneath a tent, looking on as a marching band and cheerleaders streamed forth. Japanese and Myanmar flags danced in the breeze atop the flag poles, while an array of shiny new cars—Toyota SUVs, a white Rolls Royce—adorned the freshly sealed roads (Mahtani 2015).

In many ways, the Thilawa SEZ confirms a familiar narrative about economic zones. Behind barbed-wire walls and a grand gated entranceway, the Thilawa SEZ offers manufacturers substantial investment incentives and high-grade hard infrastructures, sharply differentiating it from its surroundings in a country recently ranked 134 out of 140 in quality of infrastructure (Schwab 2015). It creates a space apart from the messiness of national politics and degraded public infrastructures: the electricity that always seems to cut out, the water that sometimes runs once a day, the roads that wash out in the rainy season. By carving out an exceptional, enclaved space that stands alone, the zone solves a problem: how to attract investment in a country of exceedingly poor infrastructure. The answer the zone provides is not, of course, broad economic stimulus through state investment in infrastructure: infrastructure for all, in a sense, as in the story of the Keynesian public provisioning of erstwhile developmental states. The answer is infrastructure for some, namely elite workers and foreign corporations. This thinned-out, more differential politics of infrastructure supposedly emerges in sharp contrast to an earlier, thicker, more inclusive politics of state-led, nationally articulated projects under developmental states (Bach 2011; Ferguson 1999, 2006; Ong 2000, 2006).

I want to suggest the story is more complicated than this. Not long after independence, the government of Myanmar, then known as Burma, convened a group of planners, policymakers, and economists—led by the American engineering firm Knappen Tippets Abbett (KTA)—to produce the country’s first major development plan, released in 1954. The plan was known as the Pyidawtha Plan, its name connoting happiness, prosperity, and material well-being in a national frame. In the wake of World War II, the plan focused heavily on the reconstruction of roads, railways, waterways, and communication systems that had been decimated in the war. Like midcentury approaches to infrastructure elsewhere under Keynesian liberalism or developmental states, the plan ties infrastructure development to a broadly egalitarian state welfarism: mixed, in this case, with overtures to Buddhist principles. “But do not forget,” the report’s closing section reads, “that the objective of all these steps—separately and together—is a Burma in which our people are better clothed, better housed, in better health, with greater security and more leisure—and thus better able to enjoy and pursue the spiritual values that are and will remain our dearest possession” (ESB Rangoon nd:10–11).

The Pyidawtha Plan resonated widely in the 1950s, even if the plan itself—a sprawling and highly technical document exceeding 800 pages, written in English and printed in London—had limited circulation in Burma. U Nu, Burma’s prime minister and leading political figure in the 1950s, hosted a Pyidawtha conference at which he gave a series of speeches introducing the plan in vernacular terms. Collected in a book edited by the poet and writer Zaw Gyi, the speeches were printed in Burmese in Rangoon. Part of U Nu’s broader attempt to forge a socialist politics consistent with Burmese cultural and religious values, the speeches aimed at cultivating support for the plan not just among technocratic elites, but also among ordinary people across the country (Than 2013). Maung Maung (1953), a public intellectual who later led, briefly, the military government, wrote that “without question, pyidawtha has caught on in Rangoon.” He described city buses carrying signs proclaiming “Pyidawtha” as their destination; children singing Pyidawtha songs in the street; and Pyidawtha coffee bars where one could buy a cup of “Pyidawtha coffee” or cold glass of “Pyidawtha milk.” Marveling at the building and rebuilding of reservoirs, roads, bridges, and schools, Maung Maung claimed that “Pyidawtha aspires not merely to develop Burma in material ways, but also to create the ‘new man,’ that is, a responsible citizen who will participate actively and constructively in government, an intelligent, public-spirited individual possessing a reasonable share of modern education.”

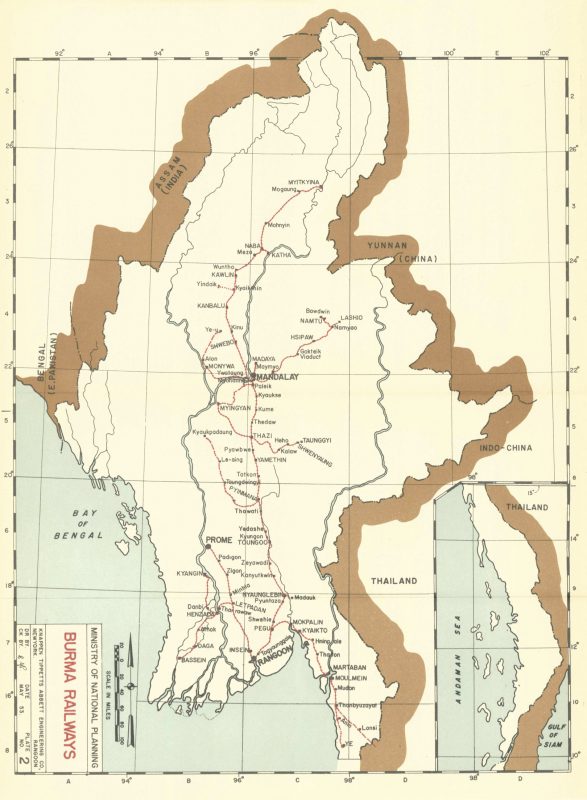

Figure 2.

Such is the universalized citizen-subject of Pyidawtha developmentalism, a “new man” for a new era. Yet beyond the public rhetoric of figures like U Nu and Maung Maung, it is hardly clear that Pyidawtha-era infrastructure development effectively cultivated this kind of inclusive national subject. One recalls, in this context, that U Nu indeed oversaw claims to an egalitarian developmental paradigm linked to a Buddhist-inflected state welfarism. But he also presided over crippling counterinsurgency campaigns in largely Christian highland areas, where his decision to make Buddhism the state religion still rankles today amid persistent civil conflict (The Irrawaddy 2014; Saw Yan Naing 2013). Chinese and Indian communities, once dominant in trade and colonial administration, also suffered acute persecution and economic discrimination, the echoes of which some see in more recent anti-Muslim violence (Brown 2013; Crouch 2014). In the Pyidawtha Plan itself, plans for infrastructure development rarely extend past the Burman Buddhist lowlands. Map after map of plans for power grids, road and rail projects, and telecommunications networks trace and retrace a skein of connections across—but not often beyond—the Irrawaddy River valley. In other words, nostalgia for the lost solidarities of developmental socialism would be misplaced. Appeals to the plenitude of “our people” invoked in the Pyidawtha vision would have to reckon with who those people are, and who they are not.

In the decades that followed the military coup in 1962, the ideal of a collective subject that may have inhered at least in the public discourse, if not the actual functioning, of Pyidawtha-era infrastructure politics disappeared altogether. The political scientist David Steinberg (2005:110) argues that by the 1990s and early 2000s, the military “used the construction of infrastructure of all varieties as demonstrations of their economic and political efficacy,” including the new capital in Naypyidaw, built ex nihilo in the plains of central Myanmar. Ian Brown (2013:184), an economic historian, writes: “(N)ew highways, bridges, dams and reservoirs, indeed a new capital city for Myanmar, rising in Burma’s historic heartland, were to be seen as impressive physical evidence of (the military’s) command of economic progress.” By the late decades of military rule, infrastructure projects had come to address a subject who would be not so much served by, provided for, or made civic-minded by such projects—better clothed and better housed, and more responsible and active as a national citizen—but rather made to be overawed, obeisant, and—not least—neither active nor agentive as a danger to military rule. Well after the rhetorics of the Pyidawtha era, infrastructure under the military symbolizes the generals’ power and prestige, a far cry from egalitarian welfarism or the making of a new postcolonial subject.

Figure 2: “Burma Railways.”

The Thilawa economic zone could be read as accentuating this shift away from Myanmar’s midcentury Pyidawtha developmentalism. However, the distinction between two politics of infrastructure—the one public and egalitarian, the other private and exclusionary, as in the conventional account of economic zones—rests upon a particular reading of developmental states. In Myanmar, it is not obvious that the developmental state can provide that point of contrast, that universalizing politics of infrastructure against which a more differential set of arrangements would draw its specificity and particularity. Without taking for granted the publics that infrastructures do or do not draw together, then and now, one might follow, instead, whom and what infrastructures actually connect or bring into relation, and how new technologies may redistribute the main actors and agencies of infrastructure differently than in the past. Three aspects of the Thilawa zone—its financing mechanisms, the users of its hard infrastructures, and the schemes used to relocate former residents of the area—help make clear what this alternative approach might look like.

First, the finances. Two features stand out: the public shareholding model used by the majority Myanmar shareholder, and the emphasis on a public–private partnership (PPP) approach by the Japanese government stakeholder. Both mechanisms incorporate actors well beyond the state and its bureaucracies, expanding and diversifying who is involved in infrastructure provisioning in Myanmar. Myanmar Thilawa SEZ Holdings Co. Ltd. (MTSH) is the majority Myanmar stakeholder, a group of nine companies that accounts for 41% of Myanmar’s 51% stake in the zone. MTSH first sold public shares in the company in March 2014, seeking to generate funds needed for the first phase of the Thilawa project (San Yamin Aung 2014). Shares sold quickly, and after an additional round of offerings and eventually listing on the Yangon Stock Exchange (YSX)—the bourse, Myanmar’s first, opened in May 2016—MTSH would sell a total of more than 3 million shares to some 17,000 shareholders (Aung San Oo 2014; MTSH 2016). After decades of government-backed infrastructure projects reliant on state funding, MTSH and its formation of a public company mark the integration of novel actors in infrastructure provisioning, from a 17,000-strong group of private shareholders to a series of companies making use of an emerging financial sector.

The PPP approach driven by Japan’s main government stakeholder, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), also reflects an enlarged role for private actors in infrastructure provision. Although itself formally of the public sector, JICA has joined many other major international development agencies in using PPPs to explicitly promote and cultivate private sector contributions to development finance, including infrastructure development. JICA’s 2014 annual report, for example, argues that government financing and development aid are insufficient to address the funding needs for infrastructure development in low-income countries, such that JICA now includes funds from partners in the private sector in the loans it makes for projects like Thilawa (JICA 2014:104). In fact, the report highlights Thilawa as a case study in JICA’s embrace of PPPs, emphasizing that JICA’s loan-making for construction activities substantially incorporates private-sector investment finance. Helping to rearticulate public and private in the context of Thilawa, JICA’s pursuit of PPPs has earned plaudits from the Myanmar government, with two key government officials recently praising JICA’s PPPs (JICA and DICA 2016; Oxford Business Group 2015). Both state they will encourage the use of PPPs to fund infrastructure elsewhere in Myanmar.

The public shareholding model and PPPs indicate the convergence of a different kind of collective, more tilted towards private finance and expertise, than that of Pyidawtha-era planning and provisioning. Those who use the hard infrastructures these financing mechanisms have helped bring into being—the pipes and wires of the zone, its roads and buildings, the adjacent port being redeveloped and integrated into the zone—account for another part of this collective. A range of companies, and indeed the workers they employ, feature prominently here, brought to the zone, as the Financial Times puts it, by “the kind of reliable electricity, water, and logistics they lack elsewhere in the country” (Peel 2013). Workers are housed in purpose-built dormitories in and around the zone; garment, electronics, and auto parts manufacturers are moving into factory spaces and installing machinery; and logistics companies are handling, inter alia, road transport, shipping, and various goods processing services. Unsurprisingly, given Japan’s leading role in financing the Thilawa zone, the manufacturers now operating there are mainly Japanese firms, as are the logistics companies (Myat Nyein Aye 2015; TMC 2016a).

JICA, for its part, specifically frames the Thilawa zone as part of the Japanese government’s “Infrastructure Systems Export Strategy.” According to this strategy, Japan supports the development of the policy frameworks and physical infrastructure needed to “promote the creation of Japanese business bases” overseas, particularly through “regional development projects beginning in the initial stages” (JICA 2014:105). In Thilawa, Myanmar’s adoption of the “Japanese model,” as JICA refers to it—part of Myanmar’s turn away from Chinese investment in large-scale infrastructure projects—allows Japan to expand its role as a driver of foreign investment and infrastructure development in Southeast Asia (ADB 2016a; Peel 2013).[1] With JICA and the Asian Development Bank (ADB), a strongly Japanese-led institution, now implementing several road construction projects linking Myanmar to Thailand and beyond, Thilawa emerges as a node in a wider spatial and material realignment, tending towards regional integration along Japanese lines.[2] This process is grounded in roads, pipes, ports, and wires that are bringing together some actors and not others—Japanese manufacturers more than Chinese heavy industrial enterprises, for example—as Myanmar rebuilds connections to key trading partners and regional production networks.

Indeed, in Thilawa as in other economic zones, the work of drawing together certain actors and agencies in the zone has also meant excluding others, a reminder that the making of enclaved spaces often involves attempted forms of disentanglement and disconnection from surrounding areas (Appel 2012). Among those excluded from the collective assembled by the Thilawa zone are former residents of the project area. In late 2013, the Yangon Regional Government evicted several hundred families from the Class A project area, after which some of those displaced grouped together and built relations with national and international civil society organizations. The resulting Thilawa Social Development Group (TSDG) issued a formal complaint to JICA claiming, among other things, that no consultations preceded evictions; that compensation has been insufficient and the relocation site unsanitary; that the government used threats and lies to make farmers sign eviction agreements; and that having proceeded as such, the resettlement process has violated Myanmar law and international guidelines, including those of JICA and the World Bank that the government insisted they would uphold (ERI 2015). The complaint triggered a JICA investigation, which TSDG criticized as “inadequate” and “overly optimistic,” that found no wrongdoing on the part of the government (Yen Snaing 2014).

In contrast to TSDG, officials and advocates of the zone have hailed the resettlement process as setting a new precedent in Myanmar, even while acknowledging some of its shortcomings. The Thilawa SEZ Management Committee (TMC), a governmental oversight and coordination body, described the resettlement process as follows:

“It is the first time in the entire history of Myanmar in conducting the relocation and resettlement of the Project Affected Persons (PAPs) according to the international standard. Since it is the first experience, it is not a perfect process; however, it is considered a success and a good learning process as the relocation was complete peacefully in accordance with the Resettlement Work Plan, which was drafted in accordance with the guidelines of JICA and the World Bank’s environment and social safeguard policies” (TMC 2016b).

In an interview soon after the evictions in 2013, Set Aung, the TMC chairman, offered a more succinct account: “This is the first experience. We can’t claim we are perfect in every step.” An analyst close to the project, meanwhile, said, “The Thilawa project is landmark, in terms of doing a proper population resettlement plan. But the problem is the government hasn’t really done things in the right order – so there is a lot of rumor and misunderstanding” (Peel 2013).

The resettlement scheme and TSDG represent a final series of collective arrangements brought into being by the zone. While the Yangon Regional Government coordinated with the TMC to implement a relocation plan reaching international standards, the evictions that resulted spurred former residents to build connections, create alliances, and form an organization, TSDG, that links them to larger and better established organizations (such as Earthrights International and Physicians for Human Rights). These two formations—one tasked with the work of exclusion and disentanglement, the other raising concerns over the terms of their displacement—underline how zones remain sites for the making of political projects, from governmental techniques for managing resettlement to strategic coalitions that may challenge how such processes unfold. A challenge of this kind, moreover, would have been all but impossible under military rule. The novelty of this politics notwithstanding, for one farmer, the removal of people from the project area is still a reminder of times past. Describing the evictions in a news report at the time, he said, “We have been under military dictatorship for such a long time—we are still in the old habits” (Peel 2013).

The old habits have a history: a history one could tell through thick and thin. After the national solidarities of Pyidawtha-era developmentalism, the military used infrastructure to project its exclusive power and prestige. Similarly, the Thilawa zone does not provide for a generalized, collective subject, but rather convenes a range of differential, sectional interests: some 17,000 private investors; state bodies now linked to private financing; and largely Japanese firms engaged in manufacturing and logistics operations. This narrative charts the progressive dissolution of the socially “thick” world of the developmental state. But what is it that dissolves? What subject—stable, firm, solid in some way—is assumed to be lost or disintegrated along the way? The boundaries of the Pyidawtha public, evident in destructive counterinsurgencies and overt Burman chauvinism, suggest that in Myanmar, at least, the mythic solidarities of the developmental state provide at best a limited counterpoint for conceptualizing a thinner, narrower politics of infrastructure today. In turn, the lack of such a counterpoint reopens the story of economic zones and the problem of their critique.

It is worth noting as well that some idea of a general good, conceived inclusively and with reference to a “people,” is not the sole province of Myanmar’s earlier developmental politics. Such concepts remain embedded in contemporary public discourse about infrastructure and SEZs. In an address to a conference of academics and policymakers, TMC Chairman Set Aung explained that SEZs can further the government’s pursuit of “equitable development in economic, social, and environmental spheres”; that SEZs’ potential to offer “top-notch hard infrastructure” must be linked “to a situation where a level playing-field can be created”; and that the goal is “people-centered, equitable, inclusive, and sustainable development” (Set Aung 2014). For Set Aung, there is no necessary contradiction between concentrating high-grade infrastructure in the zone and pursuing broad-based, inclusive developmental objectives. Serge Pun, head of the FMI Group, a leading Myanmar firm and one of the main companies that formed MTSH, has spoken of Thilawa as “the only industrial park which is planned and intended for the development of Myanmar itself” (Matsui 2013). Investing in Thilawa “in hope of contributing to job creation and Myanmar’s economic growth,” Pun differentiates Thilawa from the Dawei and Kyaukphyu SEZs in Myanmar, both heavy industrial projects tied closely to Thai and Chinese support, respectively. Thilawa, for Pun, is more consistent with a nationally framed developmental vision, an SEZ for “Myanmar itself.” Set Aung and Pun remind us that while the actors and agencies of infrastructure can change, the purposes they are said to serve—material well-being, economic growth, shared national prosperity—prove durable.

Is it thus possible to see, in Thilawa’s financing mechanisms and the zone’s hard infrastructures, an appeal or address to something equitable, shared, people-centered: a concept, that is, of a public or public interest? What might it mean for these ideas to resonate in this time of market reforms, when new connections between public and private are also premised upon eviction, resettlement, and the changing management thereof? At stake, perhaps, is less the decline or persistence of a politics of publicity, but rather the redistribution of such a politics through new technologies and different agencies: a public shareholding model, a JICA-led turn to PPPs, a shifting approach to resettlement, and a collective of investors and manufacturers who are resituating Myanmar in regional production networks. Put differently, this rearticulation of power and publics might not displace an earlier politics of infrastructure so much as represent an evolving set of arrangements. As the occasion for these arrangements to emerge, the zone itself operates as a kind of technology of liberalization, generating political and economic realignments that are changing the who and how of infrastructure in Myanmar.