There Might Be Giants

We have always been surrounded by giants. They appear in myths and fairytales, children’s literature, movies, and video games. Recently, though, giants have escaped the boundaries of fiction. Videos on TikTok of purportedly real giants on Mexican and Canadian mountaintops, and grainy, supposedly historical photographs of real giants go viral on TikTok and X. The belief in the real existence of giants has reached beyond the world of the occult, where it has long had currency, to find a wider audience. Stew Peters, for instance, a right-wing influencer and close associate of Trump administration officials, has promoted this belief, and Joe Rogan, a controversial podcaster, recently distributed a video about the real existence of giants to his eight million subscribers.

What explains the spread of this belief? For that matter, what explains the historical ubiquity of giants? Are giants merely an easy symbol of larger-than-life heroes and villains, or were they—are they—somehow real?

The possibility of this realness is impossibly vague. As if by design, they don’t fall into any clear field of inquiry. Are we talking about a group of humans with abnormally tall stature? A different species of hominid? Maybe some kind of paranormal monsters? This vagueness may be precisely the giant’s power and appeal. The giant is a seductive unknowability, an inducement to question everything. By and large, giant-believers do not hope to contribute to biology, history, or metaphysics. The gist of the discourse surrounding giants is that all is not what it seems. That scientists are fools. That authorities are liars. That giants, whatever they are, are real, and no one will admit it.

There is an irresistible connection to be drawn between this giant-

inspired distrust of the sciences and, for instance, the defunding of the National Institutes of Health and National Science Foundation, the US’s withdrawal from the World Health Organization, and many other efforts to disempower institutions of public science. Algorithmically boosting online giant content to sow antagonism against scientific expertise and institutional authority is aligned with a larger project of dismantling the public state.

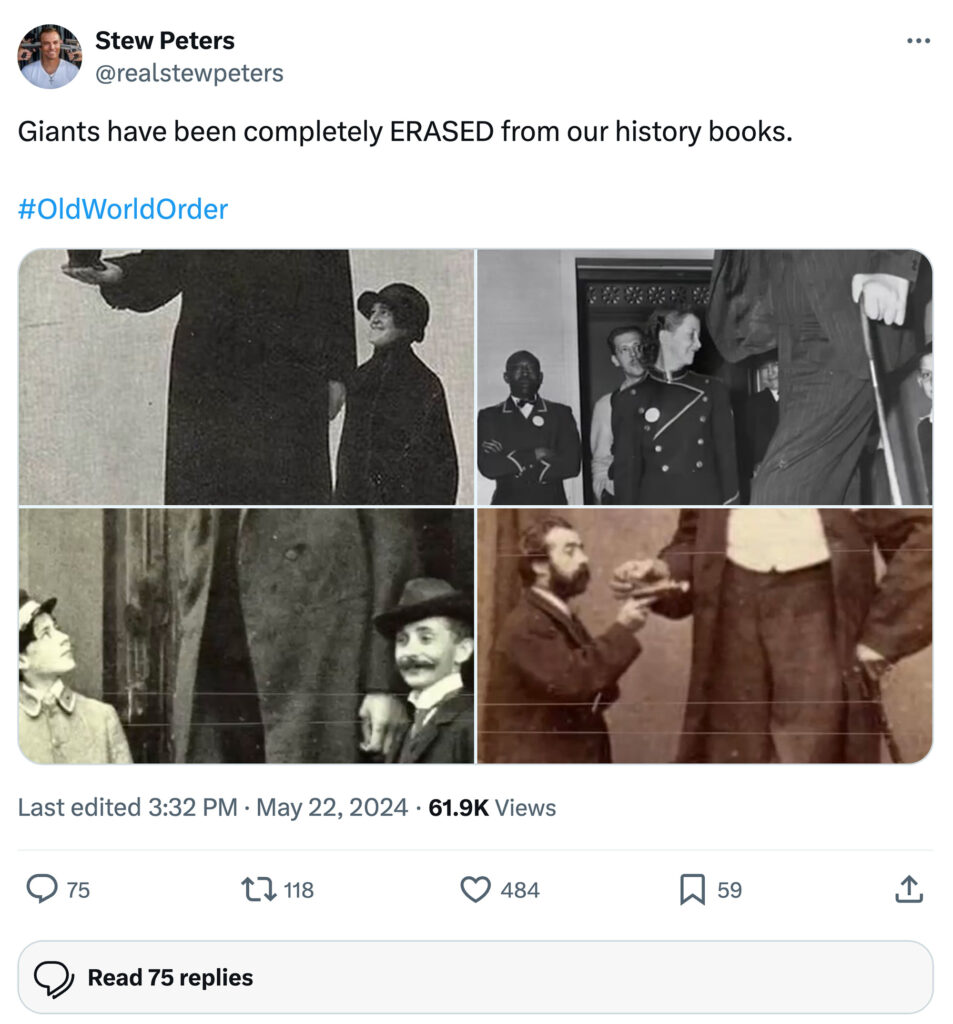

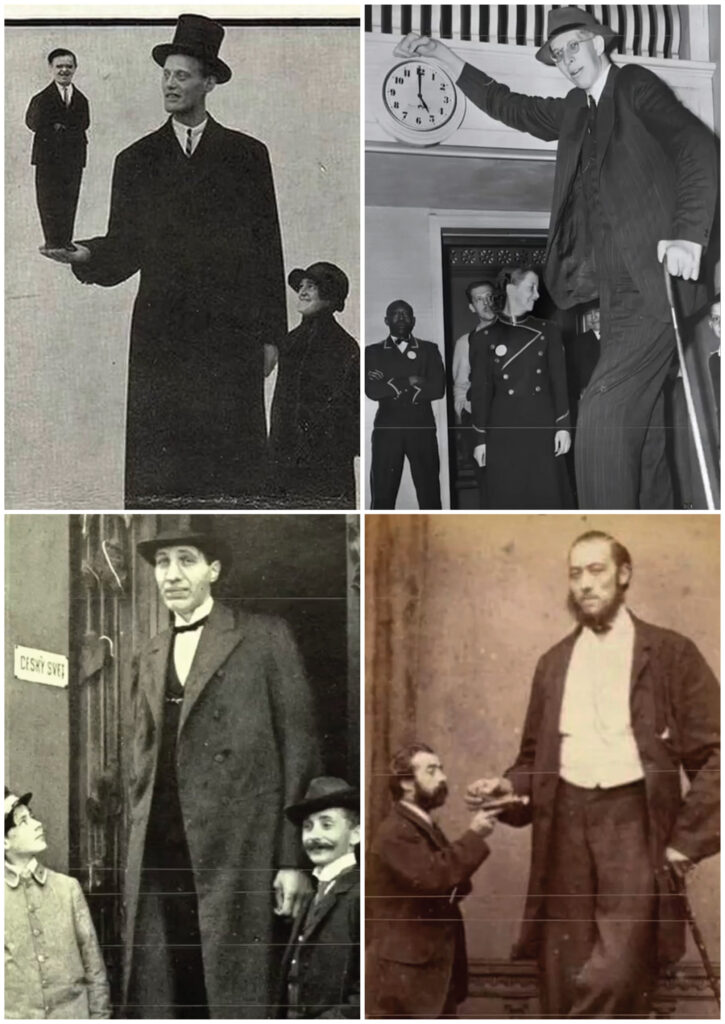

In May of 2024, Stew Peters posted a series of photos supposedly taken in the early twentieth century that featured “normally proportioned” giants beside average people. Peters, who started out as a rapper from Minnesota1, became a popular far-right personality through his podcast, in which he has promoted QAnon talking points, supported Pizzagate and flat-Earth conspiracies, espoused COVID-19 and Holocaust denialism, and engaged in violent rhetoric directed against minoritized groups. The Trump-appointed head of the FBI, Kash Patel, has been on Peters’s podcast more than a handful of times.

The images of so-called giants that Peters shared are from a YouTube “documentary” that Peters produced called Old World Order. For centuries, occultists have believed that giants built the bronze age dolmens and megalithic structures scattered across Europe. Peters’s documentary takes things much further, presenting the theory that antediluvian giants also constructed many large buildings across the world known to be built by humans in the last five hundred years, including the US Capitol building. The giant meme is uniquely suited to inducing belief in Peters’s other far-right theories.

Tweet with four uncredited images posted by Stew Peter Twitter in May 2024. Peters alleges that giants are real and evidence of them is being erased. CREDIT: TWITTER/X

The images Peters shared were almost undoubtedly produced by Midjourney or some other AI tool. Some look like early 1900s trick photography. Similar images may even be authentic—after all, there is a scientifically described syndrome known as gigantism, which causes people to grow to abnormal heights. It doesn’t matter. It is the contextualization that counts. What is important about the online discourse around giants is not whether these are real photos, but rather what the discourse represents. As Britt Paris has noted in her work on manipulated online images, decontextualized or falsified images confirm beliefs, acting as a kind of dummy evidence for whatever unsubstantiated theory adopts them. As they spread online, their ubiquity cements their apparent status as fact.

Giants are an intensifier of conspiracy theories. Belief in the vague reality of giants is essentially a refusal of the modern world in its entirety: scientific knowledge, democratic governance, liberal values. It takes far-right conspiracies beyond the arena of QAnon’s governmental divinations, and expands them into a broader rejection of scientific institutions and public reason itself. This is evident in one of the giant-believers’ most cherished conspiracy theories, namely the belief that the Smithsonian Institution is hiding a storehouse full of giants’ skeletons. The scientists “know about giants,” the theory goes, but they are unwilling to release the truth because it would verify biblical accounts of the antediluvian world.

In the European-American tradition, the giant represents a secret history and, therefore, implies distrust in authority, especially distrust of scientific institutions. To embrace the giant is to undermine the basic premise that progress moves us from mythos to logos. The reality of giants, like all literal interpretations of myths, represents a hypothesis that scientific rationale can neither prove nor disprove. The giant, then, becomes a symbol for another kind of knowing, one that is antithetical to scientific knowledge. The physical possibility of giants provides a resonant dissonance between scientific knowledge and biblical tradition in American political culture. More than UFOs or fairies or Bigfoot, the giant represents coded far-right ideology. Giants feed a particular type of biblical literalism that taps into conservative politics more directly than other myths. They create an opening for Christian nationalism, magical thinking, and belief in all manner of conspiracies that unite the Satanic with the scientific.

Still of YouTube video, “Five Discovories Proving the Existence of Giants” (“5 открытий, доказывающих существование великанов,” UPLOADED BY USER, ChanceToday, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ww-n2Kn6UfE

While a Christian nationalist like Peters might genuinely believe in the existence of giants, the meme can serve a wide set of antidemocratic ideologies. If, as Jodi Dean has argued in her recent work, the coming tech oligarchy represents a kind of neofeudalism, belief in giants can only help smooth the path. In the religious mindset implied by the reality of giants, pauperization and dispossession are not material conditions that can be changed through collective action, but rather a spiritual condition that can be religiously aestheticized and even enjoyed. Giants do, ultimately, refer back to a religious worldview.

The ubiquity of giants in mythology around the world creates its own kind of dummy evidence, making the premise more believeable. But the tradition most relevant to the online discourse under consideration here is the Adamic one. The giants of biblical myth, called the Nephilim (נְפִילִים), appear in Genesis (6:1–4) and Numbers (13:33). But, importantly, they make an appearance in the apocrypha, in the fragmentary Book of Giants, and especially in the Book of Enoch. What the Nephilim were is a mystery. We call them giants because, leaning on their own mythic tradition, that is how the ancient Greeks rendered the word (γιγάντων ) in the Septuagint, their translation of the Hebrew Bible.

Caravaggio’s depiction of David with the head of the slain giant Goliath. CARAVAGGIO, 1610, WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

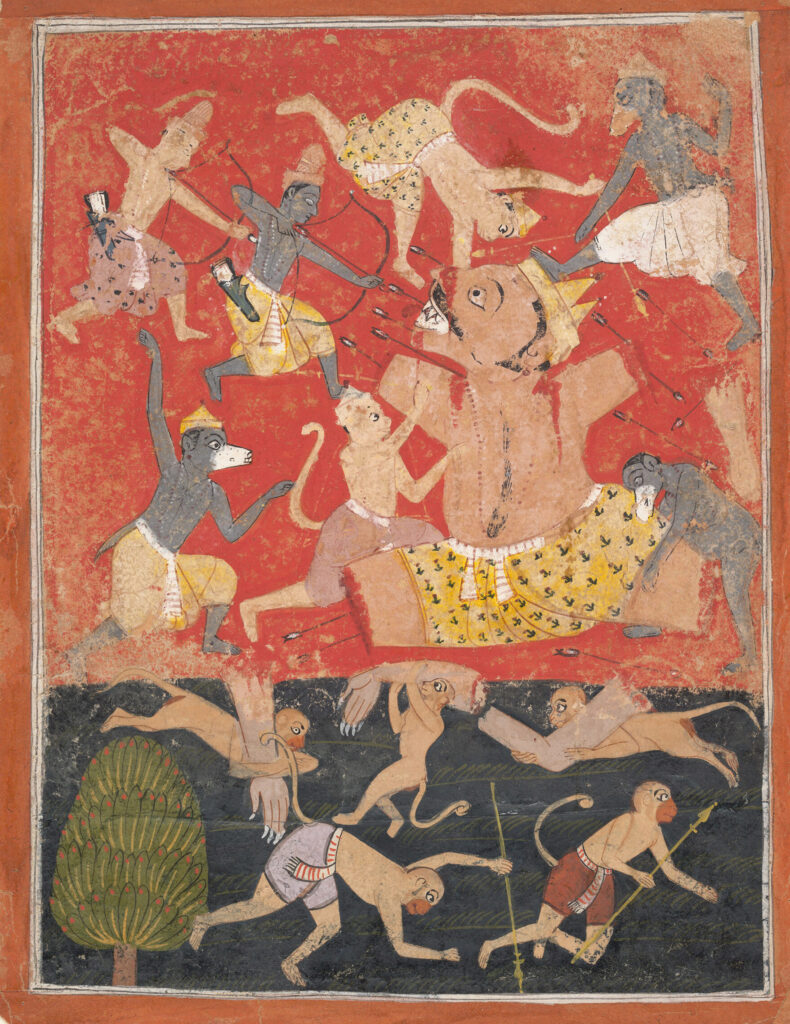

The Demon Kumbhakarna is Defeated by Rama and Lakshmana, c. 1670. COURTESY OF THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

The historical mystery of the Nephilim is amplified by their role in biblical mythology. In the Book of Enoch, the very concept of the giant Nephilim contains a promise of concealed knowledge. Enoch takes place before the Great Flood (Enoch is Noah’s great-grandfather), and it concerns the existence of a group of rebellious angels known as the Watchers. These angels defy God, descend to Earth, and interbreed with “the daughters of men,” consequently birthing the Nephilim, who are human-angel hybrids. The Nephilim murder, they deplete the Earth’s resources, and eventually they descend into cannibalism. But, most importantly, the Nephilim’s sins also include spreading secret, angelic wisdom among the humans. God sends the good angel Raphael to ensure “that all the children of men may not perish through all the secret things that the Watchers have disclosed and have taught their sons.” After the flood, the evil angels are condemned to exist as “evil spirits upon the Earth,” which is the origin of demons. The giant in Jewish and Greek mythologies indicates the reality of both secret knowledge and demonic activity among humans.

“The search for evidence of monsters will always come up short, but along the way, one may find enough reason to doubt the high narrative of reality.

The Book of Enoch is itself ironically reminiscent of the forbidden knowledge imparted by the Watchers. It was never part of the canonical Bible (except in the Ethiopian Church), even though it describes the origins of Satan and demons, which are otherwise unexplained in the Bible. To know the story of the Nephilim is to know an unauthorized, suppressed truth that is excluded from the sovereign narrative of reality. It is no surprise, then, that this text has long fascinated occultists. Queen Elizabeth I’s astrologer, John Dee, was a devotee. Today, many ufologists see parallels in the Book of Enoch to reports of UFO encounters and abductions. The giant has always been a passcode to heterodox and heretical ideas—and all the destructive and creative possibilities they may contain.

An inventory of giants in the scientific textbook Mundus Subterraneus by Athanasius Kircher, 1665. IMAGE COURTESY OF THE BRITISH LIBRARY, ARCHIVE 32.K.1, VOL.11, p.56

Anyone who seeks suppressed knowledge will find no shortage of it. There is much more to every story than what is reported in mainstream news, more even than what appears in the history books in many college curricula. No matter how commanding the knowledge of experts and authorities, there will always be other ways of knowing, other interpretations of reality. The search for evidence of monsters will always come up short, but along the way, one may find enough reason to doubt the high narrative of reality. And in the wildernesses outside this narrative, one can become subject to any manner of conspiracy theory. Giants are a gateway to the ecstasy of pure belief, unmoored to evidence. This form of belief can be used to encourage people to accept the inconsistencies of right-wing or evangelical ideology—to believe in cabals of cannibals that feast on children, to entertain white replacement theory, to deny the Holocaust, or to assert the moral inferiority of people with different bodies. If science is so biased that it cannot acknowledge giants, well, it might be worth trying a dose of ivermectin.

It’s clear why giants appeal to Stew Peters and other far-right conspiracists. Not only do the bodies of giants represent suppressed knowledge, but the story told in Enoch also invokes a eugenicist fantasy: that certain human morphologies trace their lineage back to angelic or demonic forefathers and are fundamentally different from other humans. The pedigree and epigenetic qualities of giants encourage thinking about bodies as having moral value attached to them—another hallmark of US-based evangelical Christian biblical literalism that is tightly bound to conservative politics.

Scientific knowledge and skepticism are inconvenient to many political agendas. Anti-science discourse was sown intentionally by tobacco and oil companies in the twentieth century to create a culture of denial,2 one that aligned with evangelical Christianity3 and fed into scriptural literalism and other religious fundamentalism.4 In a society that has already devalued intellectualism, science, and education, mythical thinking is powerfully seductive, and it promises a transcendental reward to those who otherwise feel disempowered.

This rejection of public reason, scientific evidence, and liberal education also follows a larger antidemocratic trajectory. Giant mythology sows distrust in public institutions, and it instills a religious framework that eases people’s ire toward the powerful while it mystifies the material conditions of life. This mythological and mystic thinking reduces epistemic friction; it facilitates the belief that scientific knowledge is demonic, and suffering is only part of God’s plan. Those who can articulate this view, like Stew Peters, can infuse into it whatever chauvinisms they choose.

And for those who own global technology platforms, energy empires, or any other precarious goods, services, or datasets, there is an even longer-term benefit in creating suspicion and distrust.5 The oligarchic elite is in the process of gutting what is left of public institutions, radicalizing social alienation, decimating the environment, and deploying scam after scam against the government and against everyday people—all aimed at amassing enough profit to engage in “manifest destiny to the stars,” as Donald Trump exhorted in his 2024 inaugural address.

As this happens, the rest of us fall into place on the lower rungs of a permanent caste system, with nothing but the giants and the angels to comfort us. To achieve such social transformation, the powerful must convince people that the scientific, commons-based, logical world is a lie, and that salvation can be found only through a private, ecstatic knowledge. Dare we suggest that these oligarchs are the real giants that must be vanquished?

- Hidden, Fokiss—I Never Made It [Official Video], YouTube, June 17, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rtSzWOG5oOw ↩︎

- Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, “Defeating the Merchants of Doubt,” Nature 465 (2010):686–687, http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/465686a ↩︎

- Darren E. Grem, The Blessings of Business: How Corporations Shaped Conservative Christianity (Oxford University Press, 2016). ↩︎

- Francesca Tripodi, “Searching for Alternative Facts,” Data & Society, May 16, 2018, https://datasociety.net/library/searching-for-alternative-facts/ ↩︎

- David Golumbia, Cyberlibertarianism: The Right-Wing Politics of Digital Technology (University of Minnesota Press, 2024). ↩︎