Twilight Shift

How does global shipping deliver thermal inequality?

Several days a week, John Ormiston clambers into his truck and delivers packages across California’s San Fernando Valley. John has been at UPS for thirteen years. The first decade was spent not behind a wheel, but in a warehouse hub, where dangerous heat exposure has become almost as common as bad traffic. He primarily worked the twilight shift, from about 5:30 in the evening until about 11 o’clock at night. “We worked in a building that was not air-conditioned,” John told me. “On hot summer days, the building would be hot, and it would stay hot well into the night.”

On a consistently clear day, the amount of solar radiation that reaches the Earth’s surface peaks around noon. Back in 1931, the playwright Noël Coward famously asserted that only “mad dogs and Englishmen go out in the midday sun.” But for those who work indoors, the hottest part of the day can arrive far later. Warehouses like the one that John worked in, which provide employment for people across the United States, absorb heat throughout the day and slowly release it into their environs as ambient temperatures drop. In turn, the working bodies in these warehouses absorb this heat. The problem for American warehouse workers is not going out at midday, but staying inside at twilight.

Those evenings were so hot, John explained, “you’d still be sweating just kind of standing around.” And he was never just standing around. “Throughout the whole ten years, every job that I’ve had has been extremely labor-intensive and physical. I’ve loaded, unloaded, but predominantly, I was a sorter. Sorting is a fast-paced job where you take boxes that are unloaded off of one conveyor belt and you put them onto a system of other conveyor belts. And that’s a very fast-paced job.”

From the perspective of commercial logistics networks, Los Angeles is a city of warehouses connected by highways and roads that facilitate the movement of boxes within boxes. Each day, shipments arrive at warehouses where they are stacked, sorted, and loaded into the cargo holds of trucks by human workers. If all goes to plan, other human workers drive these trucks across the city, delivering packages to their destinations.

But not everything always goes to plan. On July 25, 2022, Esteban Chavez Jr.—“lil Stevie” to his friends and family—was found slumped behind the wheel of his delivery truck in Pasadena, unconscious, packages undelivered. Chavez had returned to work a week earlier after convalescing from a shoulder injury, just in time for a heat wave that saw temperatures across Pasadena hitting the high 90sºF/30sºC. And only a day before, he had celebrated his twenty-fourth birthday.

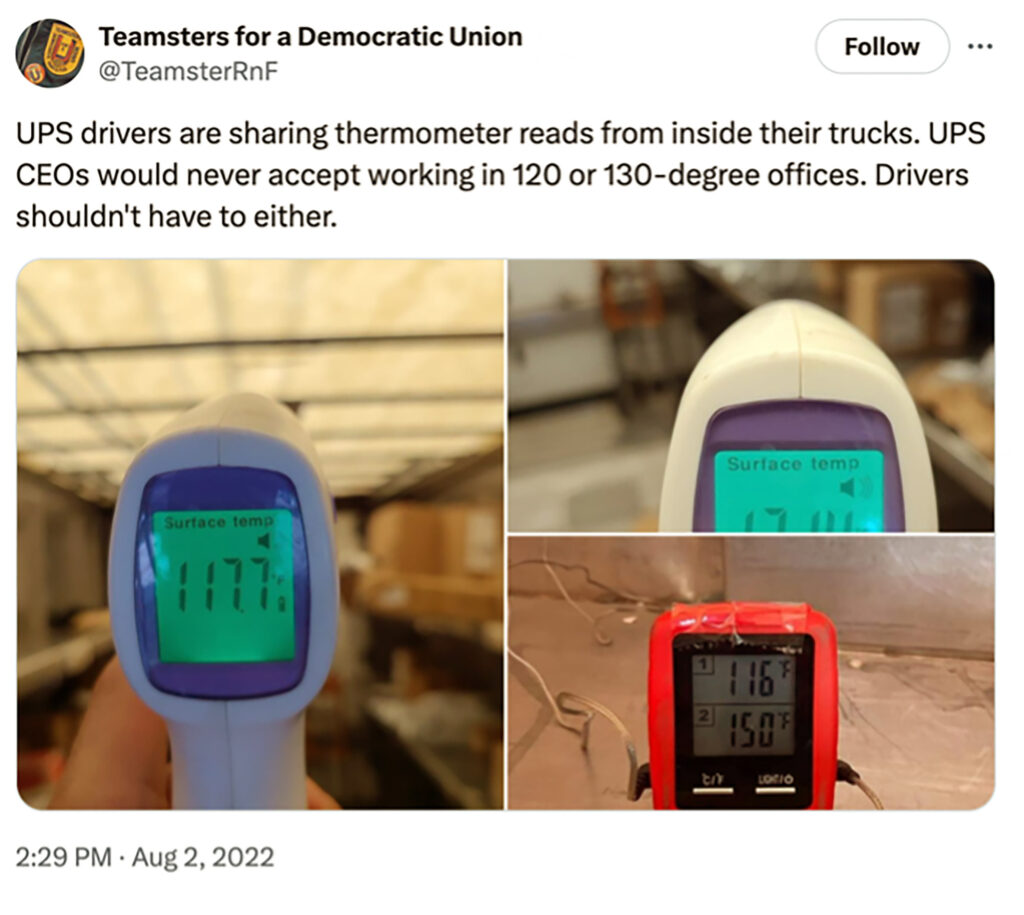

Shortly after Chavez’s death, UPS drivers began taking temperature readings inside their trucks, especially in the cargo area, revealing temperatures far above 100ºF/38ºC. As these readings were likely taken with off-the-shelf temperature guns, they have been criticized as measuring only surface temperature—of packages, the metal walls of the cargo area, etc.—rather than the heat stress experienced by workers. Nevertheless, it’s fair to say that these cargo holds were and are dangerously hot.

Delivery trucks are like warehouses in that they’re metal boxes that absorb and radiate heat. But they’re also like bodies, in that they both absorb heat and produce their own as they ply the streets. They are mobile architecture, a mass noun that’s always on the move, an indispensable part of the urban fabric (and the modern economy) as we currently live it.

None of this was news to the management at UPS. Back in 2019—three years before Chavez’s death—NBC News reported that temperatures in delivery trucks were climbing as high as 140ºF/60ºC. In response, the Vice President of Public Relations at UPS, Steve Gaut, insisted that air conditioning was an “ineffective” solution. Delivery vans, like the one in which Chavez would die a few years later, stopped and started too frequently to achieve adequate coolness.

In a social media post from August 2, 2022, a faction of Teamsters juxtaposed their working conditions with that of the managerial class: “UPS CEOs would never accept working in 120 or 130-degree offices [49ºC or 54ºC]. Drivers shouldn’t have to either.”

What their post laid out is a key dimension of what I’ve described elsewhere as thermal inequality: the unequal distribution of the negative effects of heat, in ways that frequently overlay and exacerbate preexisting forms of social harm.1 As part of a larger project, I’ve been focusing on how climate change, and heat specifically, is experienced from the vantage point of our bodies, enmeshed as they are within an economic system in which some people are made to sacrifice their health, their bodies, their very lives—what Zoé Hamstead has described as a kind of “institutionally-sanctioned violence”—precisely so that others don’t have to.2

“In the United States, those who are made most vulnerable to the heat, whose bodies and lives are rendered expendable, tend to be working-class people of color. Drivers, and not executives. Those who work in trucks, and not those who work in the C-suite.”

And it’s not just any lives. In the United States, those who are made most vulnerable to the heat, whose bodies and lives are rendered expendable, tend to be working-class people of color. Drivers, and not executives. Those who work in trucks, and not those who work in the C-suite. And, to some extent, those who deliver consumer goods, and not those who receive them at their front door. Of course, certain goods—medications, foods, technologies—must be kept in cold storage throughout the transport process to maintain their efficacy or freshness. As with the earliest iterations of mechanical climate control—used to improve production processes so that ink wouldn’t run and threads wouldn’t snap—the working body is cooled only incidentally.

Seen from this perspective, the division of labor is fundamentally, if often imperceptibly, about the distribution of thermal exposure, made all the more extreme by rising temperatures both inside and out. The homogeneously air-conditioned inside weather that the architectural historian Daniel Barber describes as the “global interior” only extends to certain kinds of indoor spaces.3 The distribution of thermal exposure is also about the division of laborers across these unevenly conditioned spaces: in other words, it is about the kinds of people that are forced into certain kinds of high-exposure jobs.4

In 2023, just over a year after Esteban Chavez Jr.’s death, members of the Teamsters Union ratified a contract with UPS, after threatening to strike during what was described as “Hot Labor Summer”—not coincidentally, the hottest summer in recorded human history up to that point. The contract stipulated that delivery vans purchased in the new year would include air conditioning in the driver’s area, although not in the cargo hold, as well as various other heat-related protections. (This was but the latest concession that UPS had made to the heat. Back in 2006, the company had introduced “Cool Solutions,” a suite of interventions to prevent heat-related illness among their workers that largely amounted to making sure that water, ice, and electrolytes were widely available, and that managers reminded their crews about the most obvious symptoms of heat-related illness.)

Just a day after the ratification of the new contract, Christopher Begley, fifty-seven years old, began to feel ill while completing his delivery route for UPS in northern Texas. As he delivered the final packages of his twenty-seven-year career, outside temperatures soared above 100ºF/38ºC. Begley was given a few days off to recover, during which time he was hospitalized and died.

When we focus on these delivery trucks, Los Angeles seems less the exception than the rule, and cities like Dallas and Indianapolis start to look more like Los Angeles than we might expect. When the center is the warehouse hub rather than a nostalgic downtown, and when you follow boxes and the people who deliver them, urban political boundaries start to fade in favor of supply chains and distribution nodes. But this is more than just an exercise in comparative urbanism. The uneasy geometry of these networks enables the distribution of heat in unequal ways, and further scrambles the porous distinctions between inside and outside. In fact, commercial logistics networks seem to multiply insides. There is an interior microclimate within the box carrying heat-sensitive medications, and within the truck that carries these boxes along with its human driver. There is also, of course, the interior of the warehouse, where packages arrive off of long-haul trucks, trains, and ships, before being redistributed along local delivery routes.

Jamison Eleuterio, a former UPS warehouse worker in Dallas (now unemployed due to a hernia he developed on the job), described to me his first week of heaving packages at the loading docks. Like John, he also worked the twilight shift. “I ended up throwing up from just the amount of heat and all the work I was doing. I was pretty miserable.”

Jamison added that he had “only” experienced acute heat-related symptoms—vomiting or pain in his chest—a few times while working at UPS. More often it was a baseline hum, a “lack of focus, where you’re just so hot and drenched. Your body—your body gets noticeably more tired working in the heat. Sometimes your skin feels like it’s getting pinched by the heat…. You do get considerably more, I guess, fuzzy in the head, because of how hot it is.”

Heat stress is about more than the heat you absorb from the warehouse. It’s also about work—the metabolic heat that your body generates to keep you alive, to make your muscles contract, to stack boxes and fill trailers. It should come as no surprise that one of the origins of the field that came to be known as occupational environmental physiology was another hot microclimate, the apartheid-era South African mines studied by physiologist Cyril Wyndham. Wyndham conducted research on Bantu, Nyasa, and other African peoples working in these mines in order to determine physiological limits to working in heat, as well as strategies for achieving optimal acclimation among different ethnic groups. His version of thermal physiology, which became globally prominent in the mid-twentieth century, was premised on ideas of racialized physiological differences.

Across the twentieth century, researchers of thermal physiology have been aware of the fact that heat is less often an event, and more often an ongoing process. Working in a warehouse, what’s far more common than heat exhaustion or heat stroke is a gradually accumulated thermal burden. Yet, physiologists have struggled to characterize the effects of these accumulated lower-level heat exposures—what Jamison experienced as tiredness, tightness, and fuzziness. Institutional ideas about safe or acceptable thresholds for heat exposure have usually been tied to an event-based conception of illness, rather than a cumulative, deteriorative understanding of heat and bodily harm. In California, the recently established indoor heat standard requires employers to provide certain remedies only when a specific temperature threshold is met: 82ºF/28ºC.5 But if you’re slowly simmering at 81ºF/27ºC, there’s no recourse.6

“For obvious reasons, they don’t want us to slow down if we don’t have to,” explained Stephen, a forty-two-year-old army vet and former UPS employee in Indianapolis (before he too suffered a shoulder injury). “But obviously, when it gets that hot, you know, some people just can’t keep up that pace.” As I heard from numerous warehouse workers, managers at UPS cajole and threaten workers to keep them working quickly, to fulfill quotas and keep boxes moving—but they also have to remain within safety quotas, measured in injuries and illnesses and days off. And the managers experience pressure to meet these quotas from their own supervisors; as Stephen put it, “crap runs downhill.”

“Buildings are soaked in heat; bodies are soaked in sweat.”

Stephen also worked the twilight shift, loading trailers. I began to realize that twilight was not simply an index of a particular time period, bookended by sunset and the darkness of night. Twilight is instead a concatenation of space, time, and labor, congealed by heat, both metabolic and environmental. Twilight offers a way of synchronizing experiences of labor in what are otherwise very different places.

“Sometimes I was just sweating so much, and I think this is true for all of us working: It felt like we jumped into a pool with all of our clothes on. We were that soaked,” Stephen said. “As the day goes on, you know, the sun is just soaked on everything. The heat just kind of gets in the building. Once everything gets hot, there’s just not nowhere else for the heat to escape. So it just soaks in.”

Buildings are soaked in heat; bodies are soaked in sweat. In writing about low-wage warehouse workers, the geographer Juan de Lara notes that “their trace—their sweat and labor—is often undetectable in the things we buy.”7 Such outlays of life and labor, central to the logistics networks that undergird much of contemporary life, are systematically effaced by an aesthetics of convenience, and by a fetish of the commodity. Some people soak in sweat, in indoor climates conditioned only by the demand for profitability, so that others don’t have to. ⦿

- Karina Brunn, Olivia Toledo, Chelsea Tran, Ashwin Vasudevan, and Bharat Jayram Venkat, “Carceral Heat Exposure as Harmful Design: An Integrative Model for Understanding the Health Impacts of Heat on Incarcerated People in the United States,” Social Science & Medicine, 367 (2025): 117679, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2025.117679. ↩︎

- Zoé Hamstead, “Critical Heat Studies: Deconstructing Heat Studies for Climate

Justice,” Planning Theory & Practice 24, no. 2 (2023): 153–72, https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2023.2201604. ↩︎ - Daniel Barber, “The Shaded Modernism of the Global Interior: Climate and Risk in the Architecture of MMM Roberto, Rio de Janeiro, 1936–1955,” in Weather, Climate, and the Geographic Imagination: Placing Atmospheric Knowledge, ed. Martin Mahony and Samuel Randalls (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020), 232–73. ↩︎

- Bharat Jayram Venkat, “Can the Subaltern Sweat?,” in The Routledge Handbook of Subalterns Across History, ed. Saurabh Dube and Ishita Banerjee (Routledge, 2025), 211–20. ↩︎

- California Code of Regulations, Title 8, Section 3396, “Heat Illness Prevention in Indoor Places of Employment.” The standard went into effect on July 23, 2024. ↩︎

- This idea is slowly changing in certain parts of the agricultural sector. See Alex Nading, “The Heat of Work: Dissipation, Solidarity, and Kidney Disease in Nicaragua,” in How Nature Works: Rethinking Labor on a Troubled Planet, ed. Sarah Besky and Alex Blanchette (University of New Mexico Press, 2019), 97–113. ↩︎

- Juan de Lara, Inland Shift: Race, Space, and Capital in Southern California (University of California Press, 2018), 90. ↩︎