“World-World” Logistics in Tangier, Morocco

On any world map, the Strait of Gibraltar is so narrow that Europe may appear to touch Africa where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean. Only nine miles across, the strait has long been a chokepoint for seaborne trade. It offers some of the earliest evidence of efforts to create common ways of containing maritime cargo in the archaeological record (Bevan 2014). Historically, ports along the strait were primarily gateways to local markets. This was the case in Tangier, which overlooks the ancient chokepoint. Here, the word “strait” conveys worldliness and appears in various local business names as the Arabic boughaz, French détroit, or Spanish estrecho. Tangier’s historical gateway function continued even as new terminal infrastructures emerged in the latter half of the twentieth century to service the new, standardized steel shipping container and its vessels. Since 2007, however, TanMed—a hub port complex (short for “Tangier Mediterranean”)—has reoriented cargo flow through the strait and introduced new types of chokepoints.

While conducting research on the transformation of Tangier’s logistics industry, I heard port administrators describe TanMed using the phrase “world-world.” Rather than a “local” gateway port into or out of Moroccan markets, the “world-world” hub port is bridging global maritime routes and elevating Morocco to a truly global scale of logistics. TanMed is designed to take advantage of the strait’s status as a maritime chokepoint linking East-West and North-South routes by offering global shipping lines a platform for transferring cargo between vessels going in different directions. In particular, TanMed has become an important intermediary point for transshipment between the large-scale vessels of East-West routes carrying consumer goods from Asia and the feeder vessels of North-South routes serving West African consumer markets. These long-distance routes of East-West trade increasingly depend on large container ships both too large and costly to stop at all but a few highly connected hub ports for transshipment, like TanMed, where containers are transferred to or from smaller, feeder vessels serving a wider range of destinations (Rodrigue et al 2017). However, despite administrators’ visions of the port as a seamless bridge for flow, bridges are chokepoints too. That is, the very act of facilitating connection and flow produces its own set of lags, bottlenecks, and other logistical complications. Indeed, Moroccan cargo flow coordinators revealed the “world-world” connection to me in relation to their everyday problems of mediating other chokepoints at the port: the mundane frictions between intersecting forms of information, material, and territory. Rather than a product of only discrete geographies and infrastructures, they reveal how chokepoints in maritime logistics can be found throughout the scales of supply-chain work.

“The Strait as Maritime Bridge” (Le détroit comme pont maritime) in the TanMed Port Authority visitors center. Janell Rothenberg

Spain and the Mediterranean viewed from the edge of a container terminal at TanMed. Janell Rothenberg

While interviewing the then-port director Mohammed in 2008 [1], I glimpsed the strait out his office window as he described how the port’s chokepoint location made it an ideal platform for transshipment. He expressed with pride that TanMed is not just a typical Moroccan port, “captive to local flows,” but is instead a hub with “world-world connectivity.” However, hub ports must also become chokepoints themselves as well-connected and indispensable platforms within larger transshipment networks. Mohammed referenced this need when telling me that they planned on “joining the map” of the most connected ports in the world. When the port welcomed the world’s largest existing containership in 2012 [2], Rachid Houari, one of Mohammed’s successors, was quoted as saying, “this event symbolizes the top-notch, international scope of this port and logistics hub, which places Morocco among the top eighteen countries in the world in terms of maritime connections” (Tanja24 2012) [3]. As a result of these changes, the TanMed Port is recognized by logistics scholars as having played a critical role in transforming the Strait of Gibraltar from “an obligatory passage point” to “an important transshipment nexus” (Rodrigue et al 2017; Rodrigue 2016). Port administrators thus echo this chokepoint-as-nexus discourse. However, while the world-world traffic of transshipment is meant never to enter Moroccan territory beyond the zones of the port, this traffic still depends on local Moroccan services of chokepoint mediation.

Since 2007, the transformation of the strait from a gateway to a hub at TanMed has happened with the help of the first generation of Moroccan cargo flow coordinators. Working for the Tangier agency of a global shipping line, Noura and her colleague Youssef are part of a rising middle class of young Moroccans in the region who moved north to participate in Tangier’s emerging logistics industry. However, anxious to facilitate the world-world traffic of transshipment through the port, they were frustrated with the pace and “mindsets” of the older generation of transportation workers, veterans of a time when imports and exports dominated regional trade infrastructure. If Noura and Youssef represent a new generation attuned to logistics and what it takes to move cargo between local and world-world scales, their experiences do not map onto those of port administrators. Rather, these coordinators experience the port’s world-world mission as an everyday problem of mediating across different kinds of chokepoints.

Noura’s work revealed chokepoints between various forms of digital and paper information and their local, national, and transnational sources. Her daily work would start with receiving worksheets from the company’s central office indicating what containers were to be discharged from which vessel. Ensuring that the terminal is notified accurately required that Noura keep a constant lookout for seemingly minor, informational discrepancies that could prevent containers from being discharged at TanMed and thus interrupting their complex, world-world routes. These discrepancies can emerge in different formats of information between the central office and the local, terminal operator, or between codes for ports and correct locations in the terminal yards. In mediating these discrepancies, Noura’s work follows a virtual map of information chokepoints between her company’s home office, its vessels, and the terminals at TanMed. Because every physical movement in logistics depends on a prior movement of information, her concern over mediating these chokepoints went beyond these particular forms and sources of information. She told me that “you have to respect” every step of logistics because “as soon as you miss an aspect from logistics, a step from logistics, that’s it. The whole chain gets messed up.” Noura’s mediation work thus was necessary to avoid the creation of further chokepoints in world-world logistics.

Youssef’s work objective is “the greatest reuse of containers” by ensuring that transshipped containers do not stay too long in TanMed’s terminals. However, he has learned that containers become immobile and damaged in many ways. Damage can include a refrigerated container that leaks or a poorly packed one that risks spoilage. These damaged containers cannot be loaded onto a vessel, but staying in the container yard racks up fees. Youssef has faced a Moroccan Customs Authority that “does not understand” that damaged, transshipped containers must be repaired outside the terminal. When world-world cargo needs to be fixed locally, Youssef says that the authority will respond saying that the port “is a free zone, we do not intervene” or that “the Moroccan state does not accept garbage.” In working with immobilized containers and cargo, he is confronted with how containers themselves can interrupt plans for cargo flow. The chokepoint that emerges between the borders of the port’s free zone and Moroccan customs territory is nested within others: between old and new forms of cargo traffic, regulation, ways of work, and scopes of action. Despite the promise of world-world connection, Youssef’s transshipped cargo must sometimes move through national chokepoints.

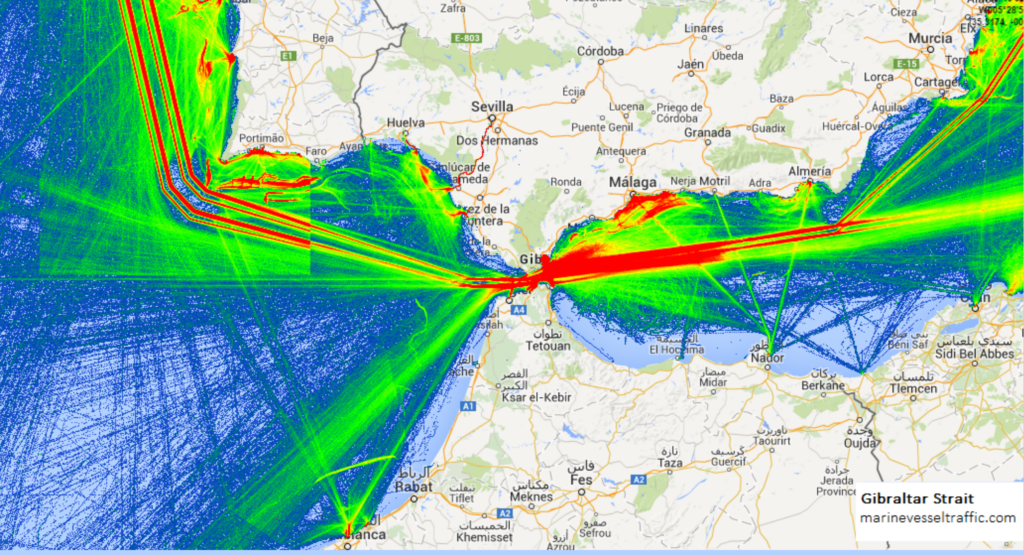

Screen shot of ship traffic through the Strait of Gibraltar, past the TanMed port. Marinevesseltraffic.com

Real-time ship traffic near Tangiers-Med Port. Vesselfinder.com

The rise of transshipment hubs as critical, momentary stops for world-world cargo means these ports are also vulnerable to any disruption. Much has been written about the portside disruptions of strikes, terror, and piracy (Cowen 2014). Yet cargo flow coordinators face other chokepoint challenges that are often just as critical, though far more banal. Port administrators like Mohammed imagined the port as a frictionless bridge across a chokepoint. Cargo flow coordinators like Noura and Youssef, by contrast, experienced the port in terms of more mundane chokepoints that can still, as Noura said, “mess up the chain.” Seen in this way, logistics coordination is an ongoing project of mediating between virtual and territorial borders and between the alternating potential of chokepoints to stop and support cargo flow. As planned or emergent sites for mediation at multiple scales, chokepoints in global logistics can thus be found at every boundary between information, things, and spaces. In going behind port hub promises for world-world connections, inquiry into how chokepoints are actually mediated can reveal the challenges of trying to jump scales from national to global forms of logistics.